A Response to the "Sacred Name" Movement

Share

Have you ever noticed how a grandmother's eyes light up differently when she hears "Grandma," "Nana," or "Meemaw"? Each grandchild might use a different name, yet each one carries the full weight of love and relationship. A lady at the congregation I used to serve (her name is Betty) had grandchildren call her by three different names—some grandchildren say "Grandma," other grandchildren say "Nana," and the neighborhood kids who've adopted her call her "Miss Betty." When asked which name was "correct," she’d always smile and say, "The one spoken with love is always right."

This simple observation opens a window into one of the most contentious debates in contemporary Christianity: What is the proper name for God, and how should we use it? The Sacred Name Movement, along with various Hebrew Roots groups, insists that calling upon God by the wrong name—or using a corrupted form of His name—could jeopardize our very salvation. They argue that "Jesus" is a pagan corruption, that we must say "Yeshua" or "Yahshua" instead, and that the divine name YHWH should be pronounced and used regularly in worship. But does the fervor over phonetics miss something deeper about the nature of names, relationships, and the God who "looks at the heart" (1 Samuel 16:7)?

This issue was recently brought to my attention by one of my readers who indicated that some "influencers" on social media are making a big to-do about the "proper name" of God, even questioning the salvation of those who use the name "Jesus" (rather than Yeshua) or who do not pronounce the divine name YHWH. This is a serious issue, and it demands a response.

The Tower of Babel Reversed

To understand this controversy, we must first grasp what Scripture teaches about names and their significance. In Hebrew thought, a name wasn't merely a label but revealed something essential about a person's character or destiny. When Abram became Abraham, it marked a transformation in his relationship with God (Genesis 17:5). When Jacob became Israel, it commemorated his wrestling with the divine (Genesis 32:28). Names matter deeply in Scripture—but perhaps not in the way the Sacred Name Movement suggests.

Consider the miracle of Pentecost, that great reversal of Babel's curse. At Babel, God confused human language to scatter humanity (Genesis 11:7-9). But at Pentecost, the apostles spoke and "each one heard them speaking in his own language" (Acts 2:6). The Parthians, Medes, Elamites, and residents of Mesopotamia, Judea, Cappadocia, Pontus, Asia, Phrygia, Pamphylia, Egypt, Libya, Rome, Crete, and Arabia—all heard the mighty works of God proclaimed in their own tongues (Acts 2:9-11).

This is profound: God's first great miracle in the church age was to ensure that every person could hear the Gospel in their own language. The Spirit didn't force everyone to learn Hebrew or Aramaic first. The name of Jesus would be proclaimed in Greek as "Iesous," in Latin as "Iesus," in Arabic as "Yasu'a," and eventually in English as "Jesus." Each translation carries the full power of the original because the power lies not in the phonetics but in the Person to whom the name points.

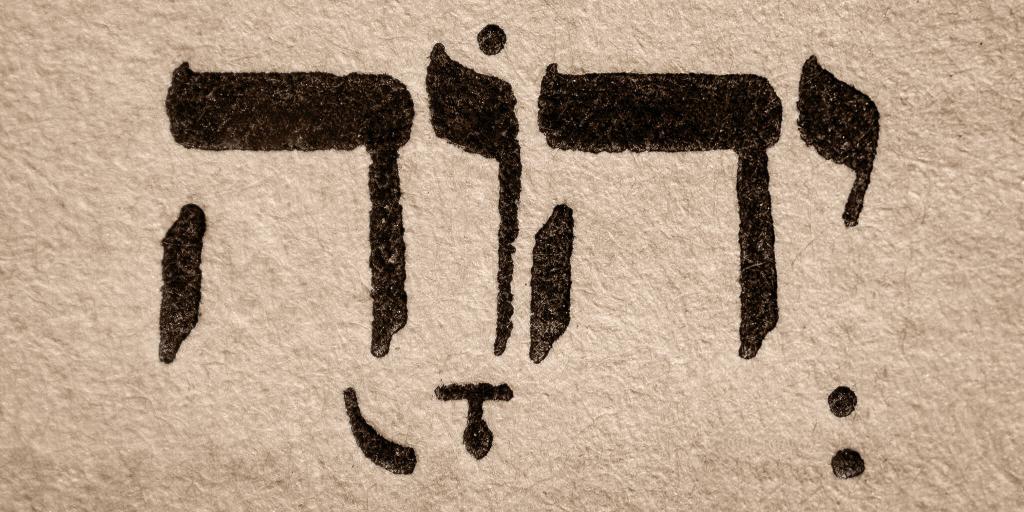

The Tetragrammaton: A Name Too Holy?

The divine name YHWH (the Tetragrammaton) appears nearly 7,000 times in the Hebrew Scriptures. Jewish tradition, developing during the Second Temple period, treated this name with such reverence that it ceased to be pronounced, substituting "Adonai" (Lord) when reading aloud. This practice influenced the Greek Septuagint, which translated YHWH as "Kyrios" (Lord), a translation pattern followed by nearly every major Bible translation today. Whenever you see LORD (all CAPS) in your Old Testament, that signals that in the original Hebrew it's actually YHWH, the "divine name" revealed to Moses at the burning bush.

The name YHWH surprisingly appears quite early in the book of Genesis, part of the Torah (the Mosaic books). For instance, after the creation account, the narrative uses the composite name "LORD God" (YHWH Elohim) starting in Genesis 2:4, establishing the name's antiquity in the biblical record. Furthermore, the name is used by early figures like Eve (Genesis 4:1) and Seth (Genesis 4:26), suggesting its knowledge was present from the beginning of humanity according to the text.

However, the Bible itself notes that a deeper, more profound understanding or significance of the name was reserved for a later time, as Exodus 6:3 records God saying to Moses: "I appeared to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob as El Shaddai (God Almighty), but by my name YHWH I did not make myself fully known to them." This suggests that while the name was known or used earlier, its full import as the God of the covenant and redemption was yet to be revealed.

The name's most famous and theologically significant revelation occurs in the book of Exodus, when Moses encounters God in the miraculous spectacle of the burning bush on Mount Horeb (Exodus 3).

When God commissions Moses to lead the Israelites out of slavery in Egypt, Moses asks for a name he can give to the people: "If I come to the people of Israel and say to them, 'The God of your fathers has sent me to you,' and they ask me, 'What is his name?' what shall I say to them?" (Exodus 3:13).

God's response is a profound statement of divine being and presence: "I AM WHO I AM" (Hebrew: Ehyeh Asher Ehyeh). God then instructs Moses to tell the Israelites that "I AM" has sent him, and critically, "The LORD (YHWH), the God of your fathers... has sent me to you. This is my name forever, and thus I am to be remembered throughout all generations" (Exodus 3:15).

The name YHWH is thus linguistically connected to the Hebrew verb hayah (to be/to become), conveying the sense of Self-Existence, Active Presence, and Eternal Faithfulness. This revelation solidifies YHWH not just as a name, but as a defining statement of God's unchanging, covenant-keeping character.

The Sacred Name Movement argues this represents a tragic loss, even a conspiracy to hide God's true name. They point to passages like Joel 2:32: "Everyone who calls on the name of the LORD will be saved," arguing that we must vocalize the exact name YHWH (pronounced as Yahweh, Jehovah, or other variations they propose) for our prayers to be heard.

Yet Jesus Himself, who certainly knew the pronunciation of the divine name, never corrected this practice. Instead, He taught His disciples to pray to "Our Father" (Matthew 6:9). In His most intimate moment of prayer in Gethsemane, He used the Aramaic "Abba," a term of familial endearment (Mark 14:36). As Saint John Chrysostom observed, "He did not say, 'When you pray, say, O God,' or 'O Master,' or 'O Lord of all,' or 'O Self-Existent One,' which are names of God, but rather 'Father,' teaching us to take confidence from the outset" (Homilies on Matthew, 19.4).

The Divine Name: Power vs. Presence

The danger of the "Sacred Name" movement is, oddly enough, that in its aversion to supposed "pagan influence" they actually are much closer to paganism than they'd like to admit. For pagans, the utterance of a particular name of a deity had particular power, some even believing that by speaking the deity's name someone could get "control" of a god, and bend his will to their purpose.

This pagan perspective, known broadly as onomancy (the belief that names have power to control) or theurgy (magical coercion of the gods), is thoroughly attested in the ancient world:

Egyptian Magic: In Egyptian mythology and magic, knowing the secret, true name of a god (such as Ra) was believed to give the possessor power over that god. For example, the myth of Isis and Ra recounts Isis tricking Ra into revealing his secret name so she could gain access to his power and secure the throne for her son, Horus. As scholar Jan Assmann notes, in this system, "The secret name is the hidden self of the god, and to know it means to possess the god's power" (Assmann, Moses the Egyptian: The Memory of Egypt in Western Monotheism, 1997, p. 28).

Greek and Roman Practices: Ancient Greek and Roman magical papyri are replete with incantations that rely on the precise, correct pronunciation of divine names to compel the gods or spirits to perform tasks. These names were often secret or deliberately rendered in cryptic ways to increase their efficacy. The very concept of the nomen sacrum (sacred name) as an object of power was pervasive.

The biblical narrative deliberately subverts this pagan desire for control, which is the very thing God refuses to give Moses at the burning bush. When Moses asks for God's name, essentially asking "What can I tell them to call you so they can control you or know your limit?" God does not give an easily pronounceable, static, or magical word. Instead, He replies: I AM WHO I AM" (Ehyeh Asher Ehyeh)

This response is a theological firewall against paganism. It is not a name that reveals a weakness or a formula for control, but a statement that reveals:

Self-Existence and Sovereignty: God's being is determined by no one but Himself.

Mystery and Unknowability: The name defies precise grammatical categorization and remains intentionally vague, asserting that God is beyond human comprehension and manipulation.

Active Presence: The name implies action—"I will be what I will be," or "I am present as I am present." It anchors God's identity not in a fixed word, but in His active, covenantal relationship with Israel.

Therefore, seeking to restore a single, magical, or correct utterance of YHWH as a prerequisite for salvation or effective prayer ironically places the emphasis on the power of the human voice and correct formula, mirroring the pagan belief systems the Bible was designed to dismantle. The biblical emphasis, confirmed by Jesus, is not on the correct vocalization of a name, but on the relationship with the Person of God the Father

The Apostles' Standard: Translation Over Pronunciation

The practice of rendering YHWH as "Lord" (Kyrios) was not a late, pagan-influenced corruption; it was the standard practice of the Jewish world before Christ, exemplified by the Septuagint. Crucially, the very Jewish apostles of Christ continued and validated this practice.

When quoting the Old Testament in Greek (the language in which the New Testament was written), the apostles readily translated YHWH into Kyrios (Lord). For instance, when Peter preaches on Pentecost and quotes Joel 2:32, he says, "Everyone who calls upon the name of the Lord (Kyrios) shall be saved" (Acts 2:21). Paul does the same in Romans 10:13. This indicates that the earliest Christian leaders, who were deeply rooted in Jewish faith and culture, shared the opinion of their Jewish predecessors that pronouncing the Divine Name was unnecessary and potentially dishonorable to God.

This belief has a basis in Semitic thought, where an intimate, personal name of a powerful being was often treated with profound reverence and reserve, lest it be "taken in vain" (Exodus 20:7) by being used carelessly, inappropriately, or in magical formula. By translating the name YHWH with the title "Lord" (Adonai or Kyrios), the emphasis shifts from the phonetic sound to the person's authority and relationship to the worshipper, thereby protecting the sanctity of the Name.

The Name of Jesus: Lost in Translation?

The argument that "Jesus" is a pagan corruption deserves careful examination. The name "Jesus" comes to us through a linguistic journey: from Hebrew "Yeshua" to Greek "Iesous" to Latin "Iesus" to English "Jesus." Each step represents not corruption but translation—the natural process by which names cross linguistic boundaries.

Consider how we handle names today. We don't insist that everyone pronounce "John" as "Yochanan," its Hebrew original. We don't correct Spanish speakers who say "Juan" or French speakers who say "Jean." The apostles themselves, writing under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, used the Greek form Iesous when composing the New Testament. If the exact Hebrew pronunciation were essential for salvation, would not the Holy Spirit have preserved it in the Greek text?

Moreover, the New Testament repeatedly emphasizes that salvation comes through faith in the Person of Christ, not through pronunciation precision. As Paul declares, "If you confess with your mouth that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved" (Romans 10:9). The emphasis falls on the confession of lordship and the heart's belief, not on phonetic accuracy.

Saint Augustine addressed similar concerns in his own day, writing: "When anyone says to his brother, 'God bless you,' he says it in the language which he and the other understand. God's blessing is not confined to one language... The sound of the words varies according to the diversity of languages, but the feeling of the heart which prompts the words is the same" (On Christian Doctrine, 2.13.20).

Misunderstood Names: False Assessments and Linguistic Leaps

Many of the names promoted by the Sacred Name movement as being the only "correct" ones are, in fact, based on false linguistic assessments of the text.

"Jehovah": This is a 16th-century Latinized hybrid name, formed by taking the consonants YHWH and mixing them with the vowels of the Hebrew word Adonai (Lord). It is a linguistic artifact, not a historical pronunciation.

"Yahweh": While this is widely considered by scholars to be the most probable original pronunciation, its reconstruction is based on late Greek transcriptions and is still a scholarly conjecture, not a divine mandate.

"Yahshua": This popular Sacred Name version of Jesus's name is a linguistic impossibility. It attempts to combine the first part of the supposed pronunciation of YHWH (Yah) with a shortened form of Jesus's name (shua), but the actual Hebrew name is Yeshua (which is a contracted form of Yehoshua), meaning "The LORD is salvation." The construction Yahshua is not attested in ancient Hebrew.

These examples show that the insistence on these specific forms often stems from modern, flawed attempts to reconstruct a language's phonetics, not from sound biblical or historical scholarship.

The Warning Against Modern "Insight"

A crucial aspect of this debate involves the spirit in which the "Sacred Names" are often promoted. Believers must be wary of any movement that claims to have an "insight" that makes them somehow more brilliant or correct than 2,000 years of Christian history. ⚠️

The idea that a truth so vital for salvation—the correct pronunciation of a name—was lost, corrupted, or deliberately hidden from the apostles, the early Church Fathers, the saints and popes, the reformers, and the millions of martyrs who died proclaiming the name "Jesus," strains credulity. This narrative of a "Great Apostasy" that only a few modern scholars have corrected is a hallmark of cultic thinking and spiritual elitism. It elevates the human pursuit of secret knowledge (gnosis) above the clear revelation of Scripture and the wisdom preserved through the Holy Spirit in the Church. The Holy Spirit has been guiding the Church (John 16:13); to suggest the whole body of Christ has been calling on the wrong name for two millennia is to deny the power and faithfulness of God.

The early Church Fathers consistently warned against those who introduced novel doctrines outside the established apostolic teaching:

St. Irenaeus (2nd Century) emphasized stability and continuity: "The tradition of the apostles, made manifest in all the world, consists in the unity of the Spirit, and not of divers tongues" (from Against Heresies, III.12.7). He viewed the Church's universal, unified teaching as the proper standard, not the secretive "insights" of Gnostics or other splinter groups.

St. Vincent of Lérins (5th Century) established a famous rule for distinguishing sound doctrine from error: "That which has been believed everywhere, always, by all" (Commonitorium, 2). Any doctrine, such as a claim regarding the correct name, that is not attested to everywhere, always, by all faithful Christians throughout history should be viewed with profound suspicion.

Tertullian (2nd-3rd Century) argued that anything new must be false, stating, "Truth does not change. What was true then remains true now. If it has always been one, it cannot have become other" (paraphrasing from Prescription Against Heretics). The claim that the essential name for salvation was only "rediscovered" in the modern era is, by this ancient standard, simply indefensible.

The Heart Behind the Name

The Sacred Name Movement, despite its errors, arises from a commendable desire: to honor God and worship Him properly. This impulse deserves respect even as we correct its misdirection. The movement's adherents often feel they've discovered something precious that mainstream Christianity has lost. They experience a renewed sense of connection to the Jewish roots of our faith and a deeper appreciation for the continuity between the Old and New Testaments.

Yet in their zeal for linguistic precision, they risk missing what Jesus called "the weightier matters of the law: justice and mercy and faithfulness" (Matthew 23:23). They strain out the gnat of pronunciation while potentially swallowing the camel of legalism. The Pharisees, after all, were meticulous about names and formulas, yet Jesus reserved His harshest criticisms for them.

True reverence for God's name involves far more than pronunciation. The Second Commandment (the Third in some Protestant enumerations) warns against taking the Lord's name "in vain" (Exodus 20:7), which the Hebrew word "shav" suggests means "emptily" or "falsely." We take God's name in vain not primarily by mispronouncing it but by claiming His authority for our own purposes, by living hypocritically while bearing the name "Christian," or by using God's name carelessly in oath-making or cursing.

The Universal Call

One of the most beautiful promises in Scripture appears in Romans 10:13: "Everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved." Paul, writing in Greek to Roman believers who spoke Latin, quotes Joel's Hebrew prophecy without any concern that something vital would be lost in translation. The promise extends to "everyone"—Greek and Jew, slave and free, barbarian and Scythian.

Imagine if salvation required mastering ancient Hebrew pronunciation. What of the Ethiopian eunuch whom Philip baptized (Acts 8:26-39)? What of the Roman centurion Cornelius (Acts 10)? What of the generations of Christians who have known Jesus through translations in thousands of languages? The Gospel is good news precisely because it transcends linguistic and cultural barriers.

As the theologian Jaroslav Pelikan observed, "The Christ who is the same yesterday, today, and forever (Hebrews 13:8) has been addressed in a multitude of names and titles throughout Christian history, each one capturing some aspect of His infinite Person while none exhausts His mystery" (Jesus Through the Centuries, p. 1).

Conclusion: The Name That Has Authority

The question isn't whether God has a name; the question is, where does God place the weight of His authority?

In the New Testament, the authority is explicitly placed on the name of Jesus Christ. It is in this name that: Apostles performed miracles (Acts 3:6); Demons are cast out (Mark 16:17); Salvation is proclaimed (Acts 4:12): "There is salvation in no one else, for there is no other name under heaven given among mortals by which we must be saved."

The apostles, following the trajectory of Pentecost, understood that God's plan was to be accessible to all nations through a universal Gospel, not restricted by a single language's phonetics. The one name that God has exalted and commanded all creation to bow to is the name that reveals His Incarnation and work on the cross: "Jesus" (Philippians 2:9-11).

Betty's wisdom remains the guiding light: God looks at the heart. Our faith is not in the precision of our tongue but in the Person to whom our heart is turned. In the end, the "name above all names" is not a secret syllable whispered in ancient Hebrew, but the title that expresses the Lordship of Christ, confessed by every tongue, in every language, with a heart full of love. Our salvation rests not on perfect phonetics, but on the perfect finished work of the One who bore the name Jesus.

In Jesus' name, no matter how you say it,

Judah