Debunking the so-called "Pagan" connection to Easter

Share

Have you ever been at a family gathering when someone confidently announced that "Easter is actually a pagan holiday" or that "Christians just borrowed it from ancient fertility festivals"? Perhaps you've seen the social media posts every spring claiming that Easter eggs and bunnies prove the holiday's non-Christian origins. These claims spread like wildfire each year, leaving many believers unsettled and wondering: Is the most important celebration of our faith really just a repackaged pagan festival?

The short answer is no—and the real story is far more fascinating than the myths that circulate about it.

A Name by Any Other Language

Let's start with the elephant in the room: the name "Easter" itself. Critics often point to this word as "proof" of pagan contamination, suggesting it derives from Eostre, an alleged Germanic goddess of spring. But here's what they don't tell you: English and German are virtually alone in using this term.

The vast majority of Christians worldwide call this holy day by names derived from the Hebrew "Pesach" (Passover): Greek-speaking Christians say "Pascha," Italians celebrate "Pasqua," the French observe "Pâques," and Spanish believers rejoice in "Pascua." This linguistic evidence alone should give us pause before accepting claims about pagan origins.

So where did "Easter" come from? The most likely explanation is refreshingly mundane. The Venerable Bede, writing in the 8th century, mentions that April was called "Eosturmonath" (Easter-month) in Old English. Just as we might say "the Fourth of July holiday," early English Christians likely referred to "the holiday in Easter-month," which eventually shortened to "Easter." The month name itself may have had pre-Christian origins (as do many of our month names), but this no more makes Easter pagan than celebrating Christ's birth in December makes Christmas a celebration of decimal mathematics.

The German "Ostern" follows a similar pattern, likely deriving from an old Germanic word for "dawn" or "east"—fitting symbolism for the resurrection, when the women discovered the empty tomb "very early in the morning, while it was still dark" (John 20:1) and as the sun was rising from the east.

Debunking the Ishtar Connection: A Geographically Impossible Link

Another frequently cited (and equally flawed) theory attempts to link "Easter" to the ancient Mesopotamian goddess Ishtar. This claim often resurfaces in online memes and amateur history videos, asserting a direct etymological and thematic connection. However, a closer look at linguistics and geography quickly dismantles this assertion.

First, linguistically, the jump from the Semitic name "Ishtar" to the Germanic "Easter" (or Eostre in its hypothetical reconstructed form) is entirely unsubstantiated by philological evidence. The two words come from entirely different language families (Semitic vs. Germanic) and show no legitimate etymological connection. There is simply no credible academic pathway for the word "Ishtar" to have evolved into "Easter" or "Eostre."

Second, and perhaps more crucially, is the geographical and cultural disconnect. The worship of Ishtar was primarily concentrated in ancient Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) thousands of years before the development of Germanic languages and cultures in Northern Europe, where the word "Easter" originated. While ancient Near Eastern cultures had widespread influence, there is no historical or archaeological evidence to suggest that the worship of Ishtar directly or indirectly influenced early Germanic spring festivals or, more importantly, the specific Christian observance of the Resurrection in that region.

The idea that Bede, writing in 8th-century Anglo-Saxon England, would have taken a word from an obscure (to him) ancient Mesopotamian deity, rather than from local Germanic linguistic traditions, strains credulity beyond breaking point. The claim of an Ishtar-Easter connection is a modern fabrication, often propagated without a deep understanding of either ancient history or linguistic development.

The Dating Controversy: Following the Moon, Not the Myths

Perhaps no aspect of Easter generates more confusion than its "moveable" date. Why does Easter jump around the calendar while Christmas stays put? Some claim this proves Easter was grafted onto pagan spring festivals that followed lunar cycles. The actual history tells a different story entirely.

From the very beginning, Christians celebrated the resurrection in connection with Passover—and for good reason. Paul explicitly calls Christ "our Passover lamb" (1 Corinthians 5:7), and all four Gospels place the crucifixion during Passover week. The Last Supper was likely a Passover meal, where Jesus transformed the ancient symbols of Israel's liberation from Egypt into the sacrament of humanity's liberation from sin and death.

The Jewish calendar is lunar, meaning Passover falls on the 14th day of Nisan. Early Christians faced a dilemma: Should they celebrate the resurrection on the actual day of the Jewish Passover (as did the Quartodecimans), or should they consistently celebrate it on Sunday, the day of resurrection?

This wasn't a question of accommodating pagans—it was an internal Christian theological debate about how best to honor both the historical connection to Passover and the theological significance of the first day of the week, when Christ conquered death. The Council of Nicaea in 325 AD didn't create Easter or borrow from paganism; it simply standardized existing Christian practice, decreeing that Easter should be celebrated on the first Sunday following the first full moon after the vernal equinox.

This astronomical calculation ensures that Easter always falls after Passover begins, maintaining the theological and historical connection while also honoring Sunday as the day of resurrection.

The Historical Evidence: What the Early Church Actually Said

If Easter were really a christianized pagan festival, we would expect to find evidence in the writings of early Christians—either defending the practice or attacking it. After all, the Church Fathers weren't shy about condemning pagan influences when they saw them. Yet what we find is exactly the opposite.

The earliest Christians wrote extensively about when and how to celebrate the resurrection, but never once do they mention competing with or replacing pagan festivals. The second-century Paschal homily of Melito of Sardis connects the celebration entirely to Passover and Exodus themes. The debates recorded by Eusebius about when to celebrate the resurrection all revolve around its relationship to Passover, not to any pagan observance.

Furthermore, the early Christians were dying for their faith—being thrown to lions, burned as torches, and crucified. It strains credibility to suggest that these martyrs, who refused to offer even a pinch of incense to Roman gods, would somehow be comfortable adopting pagan festivals wholesale and just slapping a Christian label on them.

The early Church took Paul's words to the Corinthians seriously: "What agreement is there between the temple of God and idols?" (2 Corinthians 6:15-16).

The Theology of Time: Why Timing Matters

The specific timing of Easter—in spring, connected to the full moon, always on a Sunday—carries profound theological meaning that has nothing to do with paganism and everything to do with the biblical narrative of salvation.

Spring is when Passover has always been celebrated, ever since God commanded Moses: "This month shall be for you the beginning of months..." (Exodus 12:2).

The connection to the full moon ensures maximum light for pilgrims traveling for Passover—a symbolic richness as Christians recognize Christ as "the light of the world" (John 8:12).

Sunday, the first day of the week, recalls not only the resurrection but also the first day of creation when God said, "Let there be light" (Genesis 1:3). The resurrection is thus presented as the first day of the new creation, the beginning of God's restoration of all things.

Gregory of Nyssa, writing in the fourth century, captured this beautifully: "It is the Day that the Lord has made—a day that knows no evening, whose sun will never set... It is the day of the resurrection, the day of the true light, the day of the second creation."

Living the Resurrection: What This Means for Us Today

Understanding the true origins of Easter isn't just about winning arguments or correcting historical misconceptions. It matters because it grounds our faith in historical reality rather than myth, in God's continuous action in history rather than human religious innovation.

When we celebrate Easter, we're not participating in some vague "spring renewal festival." We're commemorating a specific historical event—the resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth—that occurred at a specific time and place, witnessed by specific people whose lives were so transformed that they willingly died rather than deny what they had seen.

This historical grounding should affect how we approach our faith daily. Just as Easter's date is calculated with astronomical precision, our faith must be both firmly grounded and flexibly lived. We hold fast to the historical truth of the resurrection while allowing that truth to meet us wherever we are in life's seasons.

Moreover, understanding that early Christians carefully thought through how to celebrate the resurrection—debating, discussing, and ultimately deciding based on theological rather than cultural reasons—reminds us that our faith has always been intellectually robust. We're called to love God not only with our hearts and souls but also with our minds (Matthew 22:37).

Conclusion: An Event That Makes Its Own Season

The persistent myth that Easter is a pagan holiday fails on both linguistic and historical fronts. The global Church uses names derived from Pascha (Passover), affirming its deep, unbreakable connection to Israel's story of redemption. The early dating controversies were resolved based on theological reasoning concerning the Passover and the significance of the Resurrection Sunday, not on accommodating rival pagan festivals. The early martyrs who risked their lives to reject idolatry would never have endorsed a holiday rooted in paganism.

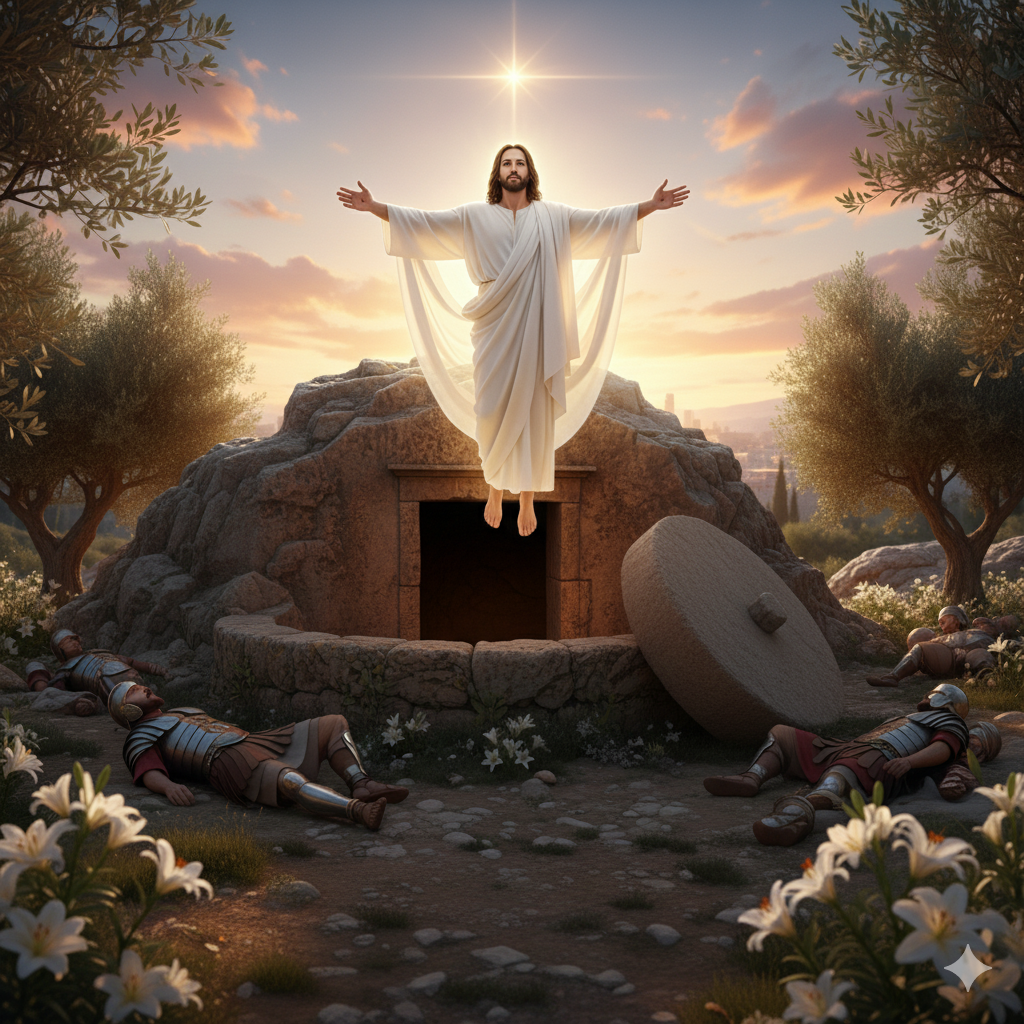

The fact is, the Resurrection of Jesus Christ is an event so utterly unique and powerful that it created its own celebration, its own season, and its own theological calendar. It is the center of the Christian year, making the season of spring sacred not because of a fleeting nature goddess, but because of the everlasting light of the Risen Christ.

The next time someone tells you Easter is "really" a pagan holiday, you'll be equipped to share the true story—one of historical integrity, theological depth, and the triumphant truth that Christ, our Passover Lamb, has conquered death. Let us celebrate the Resurrection with confidence, knowing our faith is not built on borrowed myths, but on the bedrock of history and the promise of a new creation.

He is Risen, Indeed!

Judah