Learning to Surrender: "Thy Will be Done"

Share

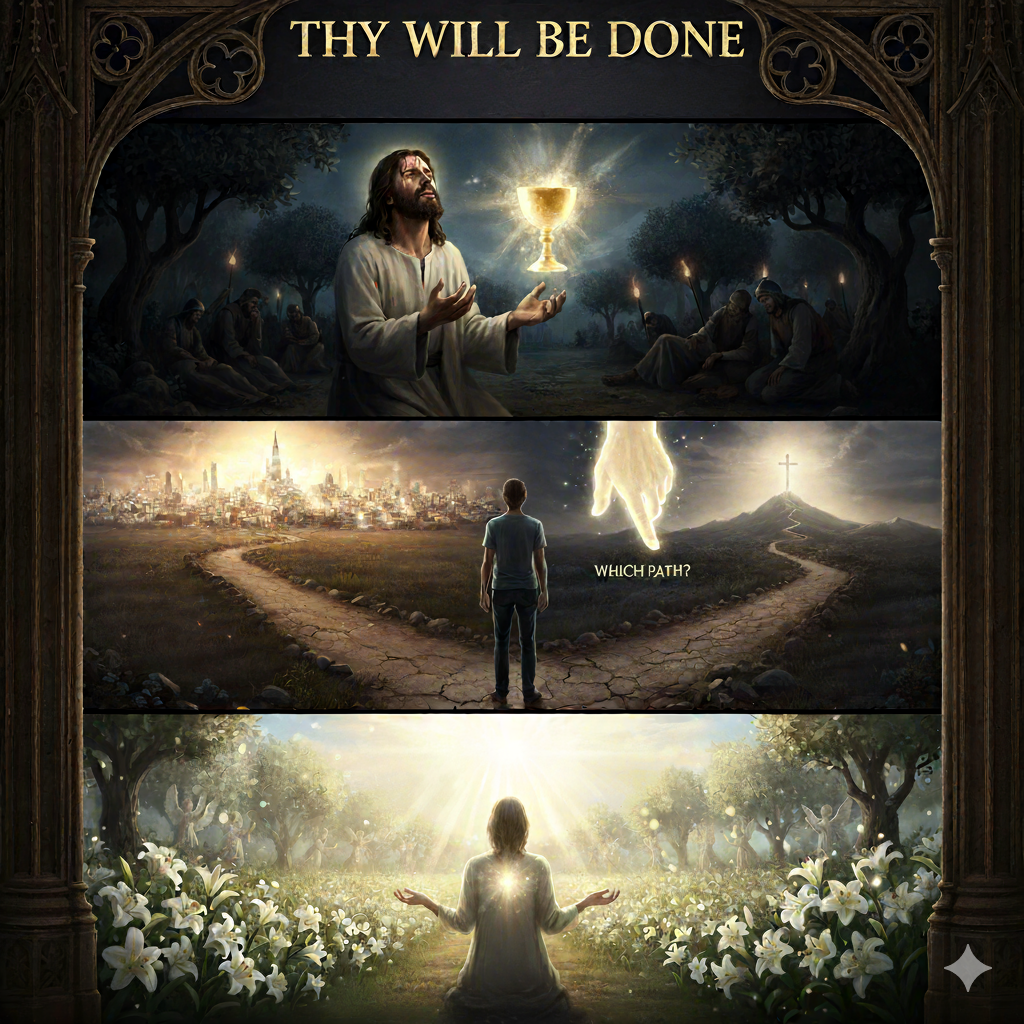

Have you ever stood at a crossroads, desperately wanting to know which path to take? Perhaps it was a job offer in another city, a relationship decision, or a medical treatment choice. In those moments, we often find ourselves praying fervently, "Lord, show me your will!" Yet how often do we add, with genuine surrender, "and give me the strength to embrace it, whatever it may be"?

This tension between seeking God's will and accepting it lies at the heart of one of the most challenging petitions in the Lord's Prayer: "Thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven" (Matthew 6:10). These six words, prayed by countless believers across centuries, contain both the summit of spiritual surrender and the daily struggle of every human heart that has ever loved God.

The Perfect Harmony of Heaven

When we pray "Thy will be done," we must first understand what we're asking. The phrase "on earth as it is in heaven" reveals something profound about the nature of God's will. In heaven, God's will is not merely obeyed—it is embraced with perfect joy. The angels do not grudgingly comply with divine commands; they delight in them. As Origen observed in his commentary on Matthew, "In heaven, God's will is not just done, but done perfectly, immediately, and with complete harmony" (De Oratione, 26.1).

This heavenly model transforms our understanding of obedience. We're not simply asking for resignation to divine decrees, but for our hearts to be so aligned with God's that His will becomes our deepest desire. Teresa of Ávila, in her Way of Perfection, captures this beautifully: "The soul that truly loves God must seek not its own will but God's alone, finding in this seeking not bondage but the truest freedom" (Way of Perfection, Ch. 32).

The Garden of Decision

Nowhere do we see the profound depth of this petition more clearly than in Jesus' own prayer in Gethsemane. The Gospel of Luke tells us that Jesus, "being in agony, prayed more earnestly, and His sweat became like great drops of blood falling down to the ground" (Luke 22:44). Here, the Son of God Himself wrestles with the weight of "Thy will be done."

The Greek word for "agony" (ἀγωνία) suggests an athletic contest, a supreme struggle. Jesus' prayer, "Father, if You are willing, remove this cup from Me; nevertheless not My will, but Yours, be done" (Luke 22:42), reveals that praying for God's will doesn't eliminate human emotion or desire. Instead, it sanctifies them through surrender.

Martin Luther, reflecting on this passage, wrote: "Christ was not play-acting in the garden. His human nature truly shrank from the cup of suffering. Yet in this struggle, He shows us the path: we bring our whole selves to God—fears, desires, and all—and then yield them to His greater wisdom" (Lectures on Galatians, 1535).

The Transformation of Desire

Thomas Aquinas distinguished between God's "antecedent will" (what God desires in the abstract) and His "consequent will" (what God permits given human freedom and the complexity of creation) (Summa Theologica, I, q. 19, a. 6). This distinction helps us understand why bad things happen even though God wills good for His creation. God's will always aims at our ultimate good, even when His providence permits temporary suffering.

Teresa experienced this truth personally through years of illness and spiritual dryness. She writes: "When we say 'Thy will be done,' we must be prepared for the Lord to take us at our word. Do not think He will treat you like a delicate flower that cannot bear the slightest wind. No, He may place you in the midst of tempests, but only to make you stronger" (Way of Perfection, Ch. 32).

This strength comes not from our own efforts but from grace. Augustine reminds us that even our ability to will what God wills is itself a gift: "God commands what He wills, and He grants what He commands" (Confessions, Book X, Ch. 29). When we pray "Thy will be done," we're asking not just for knowledge of God's will but for the grace to embrace it.

The Daily Practice of Surrender

How then do we cultivate this surrender in our daily lives? John Chrysostom offers practical wisdom: "He that says, 'Thy will be done,' can never say, 'I am in evil.' For it is not for one who does God's will to be in evil; no, nor to faint under those things that are accounted evils." (Homilies on Matthew, Homily 19).

This practice of "small surrenders" trains our spiritual muscles for larger acts of abandonment to divine providence. Teresa suggests a daily exercise rooted in this radical commitment to surrender. As she writes, the first thing the soul must do is to "deliver up its will entirely; and this entire giving, believe me, will save you a great part of your battle." This is the profound act of faith we are invited to make each morning—placing our will wholly into God's hands, confident that whatever the day brings, His purpose for us is good.

Yet we must be honest about the difficulty of this surrender. There are times when God's will seems incomprehensible, even cruel. When a child dies, when injustice prevails, when prayers seem to bounce off the ceiling—in these moments, "Thy will be done" can feel like the hardest words to pray. Luther understood this struggle intimately, having lost several children. He wrote: "God's will is sometimes hidden under a contrary appearance. Joseph in prison, Job on the dunghill, Christ on the cross—all seemed abandoned by God. Yet precisely there, God's will was being perfectly accomplished" (Table Talk, 1542).

The Paradox of Freedom and Community

One of the great paradoxes of Christian spirituality is that surrender to God's will, rather than diminishing our freedom, actually enhances it. Bernard of Clairvaux expressed this beautifully: "To will what God wills is to be truly free, for sin is slavery, but alignment with Eternal Wisdom is liberty itself" (On Loving God, Ch. 12). This freedom makes us more fully ourselves—the selves God created us to be.

It's also important to note that when we pray "Thy will be done," we don't pray alone. John Cassian, one of the Desert Fathers, taught that praying the Lord's Prayer connects us to the whole Body of Christ: "When you pray these words, you pray with Peter in prison, Paul in shipwreck, and martyrs in the arena" (Conferences, IX.18). This communal aspect offers both comfort and challenge, reminding us that we are one body striving for perfect alignment.

Conclusion: The Ultimate Intimacy

As we return to those crossroads moments, the wisdom of Ignatius of Loyola offers guidance: "In making decisions, imagine yourself on your deathbed. What choice would you wish you had made? Or picture yourself advising a beloved friend in the same situation. What would you counsel?" (Spiritual Exercises, §186). This removes the fog of self-interest that often clouds our judgment.

But beyond specific decisions, praying "Thy will be done" is about cultivating a fundamental disposition of heart. It's about moving from "God, here's my plan, please bless it" to "God, what is Your plan, and how can I participate in it?"

Teresa offers a final, profound insight: "Perfect conformity to God's will is the highest prayer, higher than ecstasies and visions and spiritual delights. For in saying and meaning 'Thy will be done,' we unite ourselves with God in the most intimate way." (Way of Perfection, Ch. 34).

To pray this petition fully is to make a covenant with God: to accept His wisdom over our own desires, His love over our fears, and His ultimate plan over our immediate comfort. It is to step out of the shadows of self-will and into the light of divine providence, finding, as the angels do, perfect joy in perfect obedience.

In Christ,

Judah