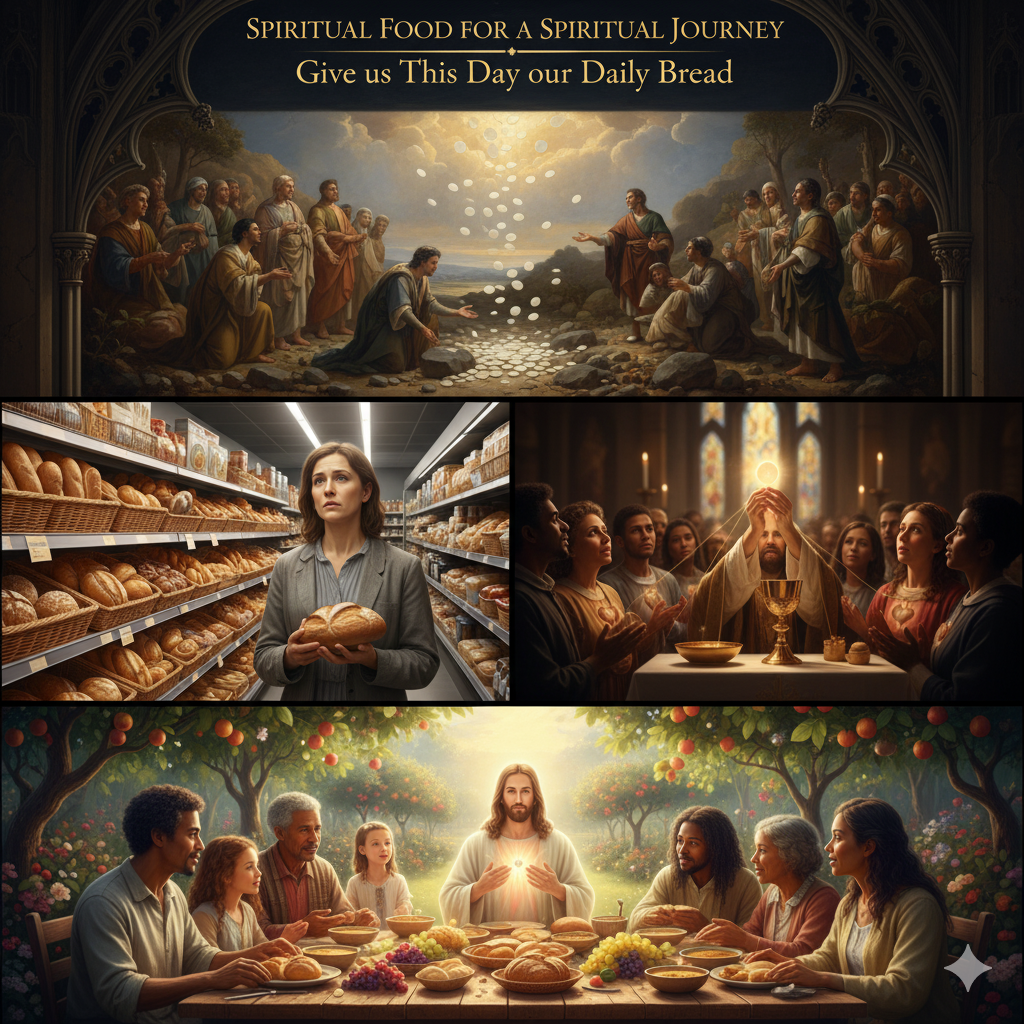

Spiritual food for a Spiritual Journey: "Give us this day our daily bread."

Share

Have you ever stood in a grocery store, overwhelmed by the endless rows of bread—sourdough, whole wheat, multigrain, artisan—and wondered what "daily bread" meant to someone who had only one kind, if any at all? In our age of abundance, we rarely pause to consider the profound weight of asking for bread. Yet this simple petition, nestled in the heart of the prayer Jesus taught us, contains mysteries that have captivated theologians for two millennia.

"Give us this day our daily bread." Seven words in English, yet they open doorways to eternity itself.

The Enigma of Epiousios

The Greek word we translate as "daily" is epiousios—a word that appears nowhere else in ancient Greek literature except in the Lord's Prayer. This linguistic mystery has puzzled scholars since the early church. Jerome, translating the scriptures into Latin in the fourth century, rendered it as supersubstantialem in Matthew's Gospel—"super-substantial" or "above-substance" bread—while using quotidianum (daily) in Luke.

Some scholars link epiousios to epienai (the coming day), implying "bread for tomorrow" or "necessary bread." Origen, the third-century theologian, believed both meanings were intended: "The bread that is 'super-substantial' is that which is most adapted to the rational nature and akin to its very substance" (On Prayer, 27.2). This ambiguity is not accidental but providential, inviting us to seek bread that nourishes both body and soul.

Echoes from the Wilderness

When Jesus taught this prayer, his Jewish listeners would have immediately recalled their ancestors' forty-year sojourn in the desert, where God provided manna—bread from heaven—each morning. "He gave them bread from heaven to eat," the Psalmist sang (Psalm 78:24). The manna was both material sustenance and spiritual lesson—what Deuteronomy calls a teaching that "man does not live by bread alone, but by every word that comes from the mouth of the Lord" (Deuteronomy 8:3).

In first-century Judaism, messianic expectations included the belief that the Messiah would restore the miracle of manna (2 Baruch 29:8). When Jesus multiplied loaves and later declared, "I am the bread of life" (John 6:35), he was deliberately evoking these expectations while transforming them.

Teresa's Insight

Teresa of Ávila, in her Way of Perfection, offers a mystical reading of this petition that harmonizes the material and spiritual dimensions. She writes: "When you have received the Lord and are in His very presence, try to shut the doors of your senses and remain with Him alone. This is supernatural bread that sustains life itself" (Way of Perfection, 34.2).

For Teresa, the "daily bread" encompasses multiple layers. While she acknowledges our need for physical sustenance, she quickly emphasizes its spiritual necessity: "The good Jesus knew what He was asking for us and how important it was for us; He saw that without this food we would find great difficulty in keeping what He had already given us" (34.6). Teresa interprets this bread primarily as the Eucharist, the supernatural sustenance that enables us to live the demanding life of discipleship.

Luther's Expansive Take

Martin Luther, in his Small Catechism, offers a remarkably comprehensive interpretation that refuses to spiritualize away the material dimension: "Daily bread includes everything that belongs to the support and needs of the body, such as food, drink, clothing, shoes, house, home, land, animals, money, goods... good government, good weather, peace, health, self-control, good reputation, good friends, faithful neighbors, and the like."

This expansive view reminds us that all of life's necessities are gifts from God's hand. Luther's insight prevents us from creating a false dichotomy between spiritual and material needs. Thomas Aquinas similarly wrote: "Under the name of daily bread, all things necessary for this life are understood" (ST II-II, q. 83, a. 12). Yet Luther also recognized the Eucharistic dimension, writing elsewhere: "These words 'daily bread' are indeed a brief expression, but they extend very far and include very much... both the physical and the spiritual life" (Large Catechism, III.72).

The Fathers' Feast of Interpretation and Fulfillment

The Church Fathers provide a several profound insights:

Cyprian of Carthage emphasized the Eucharistic nature: "We ask that this bread be given to us daily, that we who are in Christ and receive His Eucharist daily for the food of salvation may not... be separated from Christ's body" (On the Lord's Prayer, 18).

John Chrysostom emphasized the "today" aspect: "He commanded us to ask only for the bread of a single day... herein instructing us not to 'be anxious about tomorrow'" (Homily 19 on Matthew, 5).

Ambrose of Milan synthesizes multiple meanings: "This is our daily bread: the readings you hear each day in church are daily bread, the hymns you hear and sing are daily bread. These are the necessities for our pilgrimage" (On the Sacraments, 5.4.25).

Thomas Aquinas argues that while "daily bread" includes temporal necessities, its primary referent is the Eucharist: "The Eucharist is called bread because it retains the species of bread, and because it contains within itself all delight" (ST III, q.79, a.5). The significance of this petition to early Christian practice is profound; the Didache, one of the earliest Christian writings (c. 50-120 AD), instructs believers to "pray thus: 'Our Father...' three times a day" (Didache 8:3). This regular, rhythmic prayer would have deeply embedded the petition for "daily bread" into the daily spiritual discipline of the first Christians.

When we pray "give us this day," we echo the disciples at Emmaus who begged the stranger to stay: "Abide with us" (Luke 24:29). Their eyes were opened in the breaking of bread—the same bread we seek daily, the presence of Christ himself.

Living the Mystery Today

What does this petition mean for us, navigating our modern wilderness of abundance and anxiety?

Radical Dependence: It calls us to recognize our dependence. Whether our pantries are full or empty, we remain beggars before God. The petition teaches us to receive each day's provision—material and spiritual—as gift, not entitlement.

The Quest for True Satisfaction: It invites us to seek the bread that truly satisfies. In a culture of endless consumption, we're challenged to ask: What hunger are we really trying to fill? Gregory of Nyssa wrote: "He who is nourished by the true Bread of Life is not consumed, but rather, by feeding on it, is converted into it" (On the Lord's Prayer, Sermon 4).

Communal Responsibility: It summons us to become bread for others. If we truly receive Christ as our daily bread, we're transformed into what we receive. Cyprian notes that we pray "give us" not "give me"—reminding us that God's provision is meant to flow through us to the wider community, transforming us from hoarders into channels of grace.

Conclusion: The Prayer of the Pilgrim

The petition "Give us this day our daily bread" is the Prayer of the Pilgrim. It acknowledges that we are still in the wilderness, relying moment by moment on a divine supply. It is a profound act of faith that defeats both anxiety and materialism.

We pray against the temptation to hoard (like the manna), trusting the Father to meet our needs today. We pray against the temptation to forget our true hunger, remembering that only Christ can satisfy the deepest yearnings of the soul. In this simple request, we find ourselves at the crossroads of heaven and earth, asking for the material grace to sustain our bodies and the super-substantial grace to preserve our immortal souls for the journey home.

In Christ,

Judah