Summary of the Ascent of Mount Carmel (Made Simple)

Share

Have you ever noticed how tightly we grip our coffee cups in the morning, as if letting go would mean losing something essential to our day? Or how we clutch our phones, scrolling endlessly through streams of information, afraid we might miss something important? This simple, everyday grasping reveals something profound about the human condition—we are creatures who instinctively hold on, accumulate, and attach ourselves to things, experiences, and even ideas. Yet what if the path to receiving everything we truly desire requires us to first open our hands and let go?

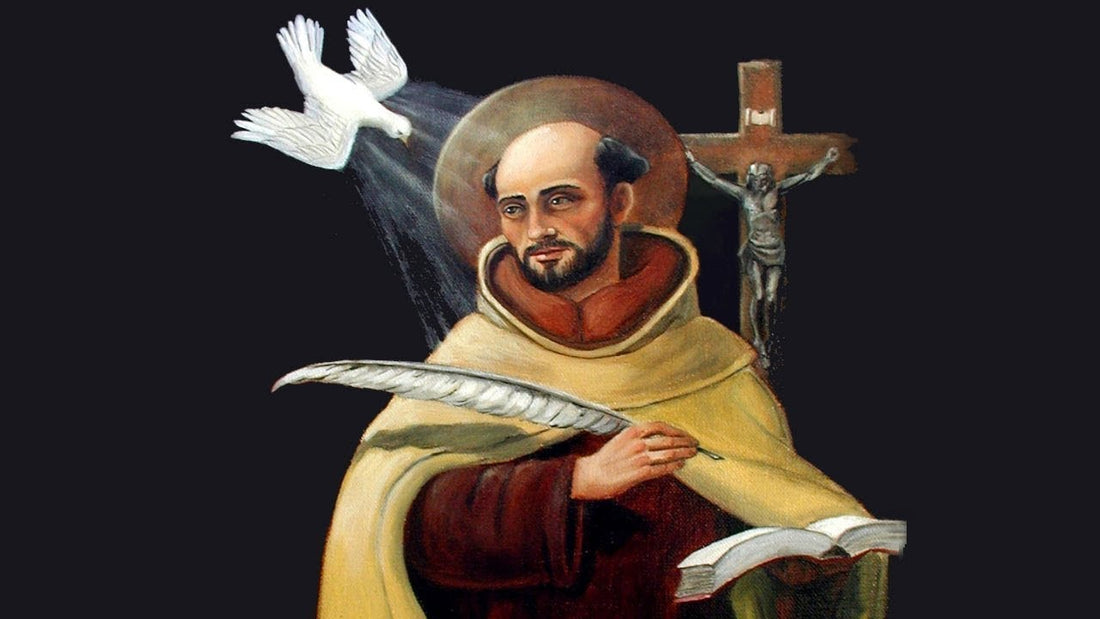

This paradox sits at the heart of one of Christianity's most challenging and transformative spiritual classics: The Ascent of Mount Carmel by St. John of the Cross, the 16th-century Spanish mystic and reformer. His work presents a radical proposition: the soul's journey to union with God requires a deliberate and systematic detachment from all created things—not because creation is evil, but because our disordered attachments to it prevent us from receiving the infinite gift that God wishes to give us.

The Architecture of Ascent

John of the Cross structures his masterpiece around the metaphor of climbing a mountain—specifically, Mount Carmel. But this is no ordinary climb; the path he describes is interior, leading through what he calls the "dark night" of purification toward the summit of divine union. He presents this journey as having three main stages, corresponding to three kinds of spiritual goods we must learn to hold lightly:

Temporal Goods: Possessions, wealth, and worldly pleasures.

Natural Goods: Beauty, intelligence, talents, and physical senses.

Spiritual Goods: Consolations in prayer, visions, and religious experiences.

What makes John's approach particularly striking is his insistence on "nada"—nothing. His famous sketch of Mount Carmel shows only one path to the summit, marked repeatedly with "nada, nada, nada" (nothing, nothing, nothing). This isn't nihilism; it's a recognition that in comparison to the infinite God, all created goods are "less than nothing" because they can become obstacles to receiving the Everything that is God Himself.

The Biblical Foundation of Detachment

John's teaching, while seemingly severe, is deeply rooted in the paradoxical nature of Scripture. Jesus Himself declared, "Whoever wishes to come after me must deny himself, take up his cross, and follow me. For whoever wishes to save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake will find it" (Matthew 16:24-25, NAB).

Consider the rich young man (Mark 10:21). John of the Cross would diagnose his failure as a classic case of disordered attachment—not that wealth itself was evil, but that the young man's grip on it prevented him from grasping the infinitely greater treasure offered in following Christ.

The Apostle Paul exemplified the resulting freedom when he wrote, "I have learned to be content with whatever I have... I can do all things through him who strengthens me" (Philippians 4:11, 13, NRSV). This is not stoic indifference but Christian detachment—the ability to receive all things as gift while holding them lightly enough to let them go when love demands it.

The Psychology of Attachment

John of the Cross demonstrates remarkable psychological insight. He explains that when we become inordinately attached to something, our soul takes on the qualities of that thing. Attach yourself to earthly, temporary goods, and your soul becomes earthly and temporary in its aspirations. As St. Augustine wrote, "You have made us for yourself, O Lord, and our hearts are restless until they rest in you" (Confessions, I.1). Every lesser attachment is a futile attempt to satisfy this infinite longing with finite goods.

John uses the vivid image of a bird tied by a thread. Whether the thread is thick or thin, the bird cannot fly until it breaks free. Similarly, any disordered attachment, no matter how small, can prevent the soul from soaring to God. This challenges the common assumption that spiritual progress simply means avoiding major sins while accumulating minor virtues and consolations.

The Active Night of the Senses

The practical program John outlines begins with the "active night of the senses"—our deliberate effort to moderate our appetites and desires. This isn't harsh asceticism for its own sake, but about recalibrating our spiritual taste buds.

John provides concrete, challenging counsel:

Choose always what is less pleasurable rather than more.

Choose what is harder rather than easier.

Choose to want nothing rather than something.

Before dismissing this as masochistic, consider its countercultural freedom. How much anxiety do we experience trying to optimize every choice, maximize every pleasure, and extract every possible benefit? John's path offers liberation from the tyranny of insatiable desire.

Spiritual Goods and the Danger of Pride

Perhaps most challenging is John's warning that attachment to spiritual goods—consolations in prayer, mystical experiences, or even our own perceived virtue—can become the subtlest and most dangerous obstacles to union with God. The person who takes pride in their prayer life or becomes attached to spiritual sweetness may be further from God than the humble sinner who knows their need.

This teaching finds echo in Jesus' parable of the Pharisee and the tax collector (Luke 18:9-14). John of the Cross would say the Pharisee was attached to his spiritual goods, while the tax collector had achieved the poverty of spirit that Jesus calls blessed (Matthew 5:3).

Practical Applications for Daily Life

The journey up Mount Carmel is a daily practice, not a heroic one-time effort. How can we apply the wisdom of "nada" to our busy, modern lives?

The Digital Fast: Practice voluntary detachment from your phone and social media. Leave your device in a different room for set periods. This trains you to endure the discomfort of "missing out" and frees your attention for reality and presence.

Practice Gratitude and Release: When you receive a gift (a compliment, a possession, a lovely moment), practice acknowledging it, thanking God for it, and then releasing your claim on it. Recognize that it is a temporary loan, not a permanent possession.

Choose the Harder Path in Small Things: When faced with two morally neutral choices, occasionally choose the one that involves a bit more inconvenience or self-denial (e.g., walking instead of driving, choosing simplicity over luxury). This trains your will to prioritize detachment.

Guard Against Spiritual Greed: When prayer is sweet, don't cling to the feeling. When it is dry, don't despair. Seek God himself, not the feeling of God. Remind yourself that the goal is not consolation but conformity to Christ.

Conclusion

The ultimate fruit of St. John of the Cross’s path of detachment is not emptiness but fullness, not poverty but infinite wealth. He writes that the soul who achieves this holy indifference possesses all things in God more perfectly than if it grasped at them possessively. This echoes Paul’s paradoxical description: "as having nothing, and yet possessing everything" (2 Corinthians 6:10, NRSV).

A clenched fist can hold only what it can grasp, but an open hand has infinite capacity to receive whatever is given. The spiritual life is fundamentally about creating space within the soul. By courageously embracing the path of nada—by choosing simplicity over complexity, silence over noise, and God over His gifts—we trade our finite, cluttered capacity for an infinite, God-filled capacity.

It is in the surrender of our tightly-held desires that we finally discover the freedom to hold Everything—the Divine Love that is the very summit of Mount Carmel.