The Myth of "The Greek Word Means...": A Deeper Look at Biblical Interpretation

Share

Have you ever been in a heated discussion where someone pulled out their phone, looked up a word definition, and declared victory? "See? The dictionary says it means this!" Perhaps it was about whether a tomato is technically a fruit or a vegetable, or what "literally" really means in modern usage. We've all witnessed—or participated in—these moments where we assume that finding a definition settles everything. But then someone mentions that "awful" used to mean "awe-inspiring" rather than "terrible," and suddenly we realize that words are more slippery than we thought.

This same challenge confronts us when we approach Scripture. In our age of instant information, where Greek and Hebrew dictionaries are just a click away, it's tempting to think we can unlock the Bible's mysteries with a simple word search. Armed with a concordance and confidence, we might declare, "The Greek word here means exactly this!" Yet this approach, sometimes called "theology by concordance," can lead us astray in profound ways. It's not wrong to say a Greek word means this or that, but most words have a "semantic range" of meanings rather than a single definition. To determine what a word implies in a text requires more than a concordance or dictionary definition. It requires nuance and a broader understanding of context (more on that below).

The Living Nature of Language

Consider how dramatically language shifts even within our own lifetimes. If you told someone in 1950 that you needed to "reboot" after "downloading" too much information from a "webinar," they would have no idea what you meant. The word "gay" meant something entirely different to our great-grandparents than it does today. "Text" was only a noun until recently; now we use it as a verb constantly. If language changes this dramatically within decades, imagine the chasm between us and the ancient world.

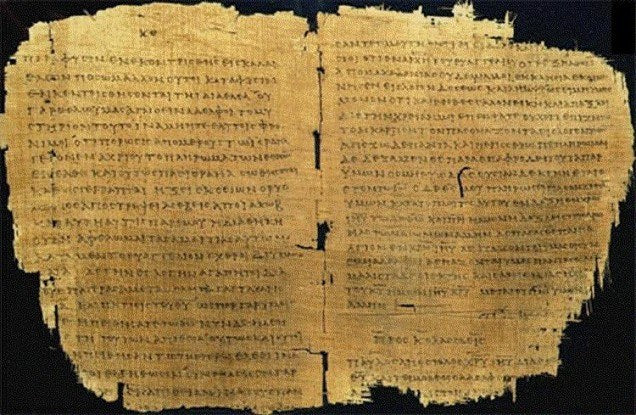

The biblical languages—Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek—were living languages used by real people in specific times and places. When the Apostle Paul wrote his letters, he wasn't consulting a dictionary to ensure theological precision; he was using the common Greek of his day to communicate profound truths to diverse communities. The Gospel writers chose their words not from lexicons but from the living vocabulary of their time, shaped by Jewish thought, Hellenistic culture, and the revolutionary message of Christ.

The Baptism Debate: A Case Study in Complexity

Take the ongoing debate about baptism. Some Christians insist that because the Greek word "baptizo" means "to immerse," baptism must involve complete submersion in water. This seems like straightforward logic: find the definition, apply it consistently, case closed. But this approach overlooks crucial evidence from the early Church.

The Didache, one of the earliest Christian documents outside the New Testament (likely written between 60-120 AD), provides instructions for baptism that would surprise many modern readers: "Now concerning baptism, baptize thus: Having first taught all these things, baptize into the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, in living water. But if you have not living water, baptize into other water; and if you cannot in cold, then in warm. But if you have neither, pour water three times upon the head" (Didache 7:1-3).

Here we have Greek-speaking Christians, possibly just a generation removed from the apostles if not contemporary to them, explicitly stating that "baptizo" can be accomplished by pouring. Were they ignorant of their own language? Are we supposed to believe that a preacher today with his concordance understood Greek better than they did? Or does this suggest that the word carried a broader semantic range than our dictionaries might indicate?

Furthermore, we find in Scripture itself uses of "baptizo" that don't fit the simple "immersion" definition. In Luke 11:38, a Pharisee is astonished that Jesus didn't "baptize" (wash) before dinner—surely not suggesting full-body immersion before a meal. In 1 Corinthians 10:2, Paul says the Israelites were "baptized into Moses in the cloud and in the sea," yet they passed through on dry ground. The word clearly carries metaphorical and ceremonial meanings beyond physical immersion.

The Myth of the Three Loves

Another popular example of concordance theology involves the "three Greek words for love": "eros" (romantic love), "phileo" (friendship love), and "agape" (divine/unconditional love).

Countless sermons have been preached distinguishing these terms, particularly emphasizing that agape represents God's special kind of love. While these distinctions can be helpful pedagogically, and I've even used them theologically (the words do tend toward these definitions) they don't hold up under scrutiny since the words can sometimes be used interchangeably in the Bible.

In John 21:15-17, Jesus asks Peter three times if he loves Him, and many preachers have made much of the supposed shift between agape and phileo in this passage. Yet when we examine Greek literature broadly, we find these words used interchangeably. Even more troubling for the neat categorization: in 2 Samuel 13:1-15 (in the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures), Amnon's lustful desire for his half-sister Tamar—which leads to rape—is described using agape!

Clearly, the word doesn't automatically always mean "divine unconditional love."

The Gospel of John itself uses these terms fluidly. In John 3:35, the Father "agape-loves" the Son, but in John 5:20, the Father "phileo-loves" the Son. Are these describing different qualities of love within the Trinity? That would be theologically problematic. More likely, John is simply using synonyms for stylistic variation, as any good writer might.

Context: The Master Key

If individual word definitions can't unlock meaning, what can? The answer is context—layers upon layers of context. We must consider:

Literary Context: How does the word or phrase function within the sentence, paragraph, chapter, and book? What is the author's overall argument or narrative purpose? In Romans 3:23, when Paul writes that "all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God," we understand "all" in the context of his broader argument about universal human sinfulness and need for redemption, not as an absolute statement including Jesus Christ, who is clearly excepted elsewhere in Paul's theology.

Historical Context: What was happening when this text was written? Who was the audience? What issues were they facing? When Paul addresses meat sacrificed to idols in 1 Corinthians 8, we need to understand the social and religious dynamics of ancient Corinth, where refusing such meat at social gatherings could mean exclusion from professional guilds and social networks.

Cultural Context: What cultural assumptions and practices inform the text? When Jesus speaks of taking up one's cross (Matthew 16:24), His original audience would have immediately thought of the Roman practice of forcing condemned criminals to carry their crossbeam to the execution site—a vivid image of shame, suffering, and death that we might miss without historical knowledge.

Canonical Context: How does this passage relate to the whole of Scripture? The principle of the "analogy of faith" suggests that Scripture doesn't contradict itself when properly understood. Therefore, our interpretation of any single passage must cohere with the broader biblical witness.

The Humility of Interpretation

This complexity shouldn't discourage us from studying Scripture—quite the opposite. It should inspire a humble, careful, and communal approach to God's Word. As St. Jerome, the great biblical translator, wrote: "Ignorance of Scripture is ignorance of Christ" (Commentary on Isaiah, Prologue). Yet he spent decades learning Hebrew and consulting Jewish scholars to better understand the text. His humility in approaching the sacred text should be our model.

The Ethiopian eunuch in Acts 8 provides another instructive example. Here was an educated man, likely fluent in Greek, reading from Isaiah. Yet when Philip asked if he understood what he was reading, he replied, "How can I, unless someone guides me?" (Acts 8:31). He recognized that access to the text itself wasn't sufficient; he needed the wisdom of the interpretive community.

This is why the Church has always emphasized the importance of tradition and teaching authority alongside Scripture. As St. Vincent of Lérins noted in the fifth century, Scripture is "sufficient of itself for everything," yet because of its depth, "all do not understand it in one and the same way" (Commonitorium, 2.5). We need the wisdom of those who have gone before us, the insights of the community of faith, and the guidance of the Holy Spirit.

Practical Applications for Today

So how do we apply this understanding to our own study of Scripture?

1. Embrace humility: Approach the Bible with the recognition that you're handling an ancient text that requires careful study. Be suspicious of interpretations that seem too neat or that conveniently align with your preconceptions. As Proverbs 3:5 reminds us, "Trust in the Lord with all your heart and lean not on your own understanding."

2. Read widely within Scripture: Don't build doctrines on isolated verses or words. Look for themes and patterns throughout the Bible. If your interpretation of one passage contradicts the clear teaching elsewhere, reconsider your understanding.

3. Consult commentaries and historical interpretations: Humble yourself by reading what others have written about the text, both ancient and modern. Give special priority to those writing in close proximity to the biblical text, such as the early Church Fathers, as they were steeped in the language and culture of the time. Look for interpretations that are consistent throughout history and aren't innovative, modern, or only a few decades old. This helps us avoid novel ideas that may not align with the historic Christian understanding of the Bible.

4. Consider an author's unique "word use": When doing literary context, start with the most immediate context and work outward. First, examine how the author uses a particular word or phrase within the same chapter, then expand to the same book or letter, and only then to other writings credited to the same writer. The nearest context always provides the best data for understanding a writer's intended meaning.

Conclusion

Navigating the complexities of biblical interpretation is not about finding a single, magic key to unlock every mystery. It's about approaching the text with humility, intellectual rigor, and a communal spirit. By moving beyond simple word searches and embracing the layers of context—literary, historical, cultural, and canonical—we can avoid common pitfalls and arrive at a richer, more faithful understanding of Scripture. The goal is not to prove a point, but to genuinely listen to the voice of God as it has been heard by the community of faith for thousands of years. This journey of discovery requires patience, a willingness to be guided by others, and a deep respect for the living, breathing nature of God's Word.

God Bless,

Judah