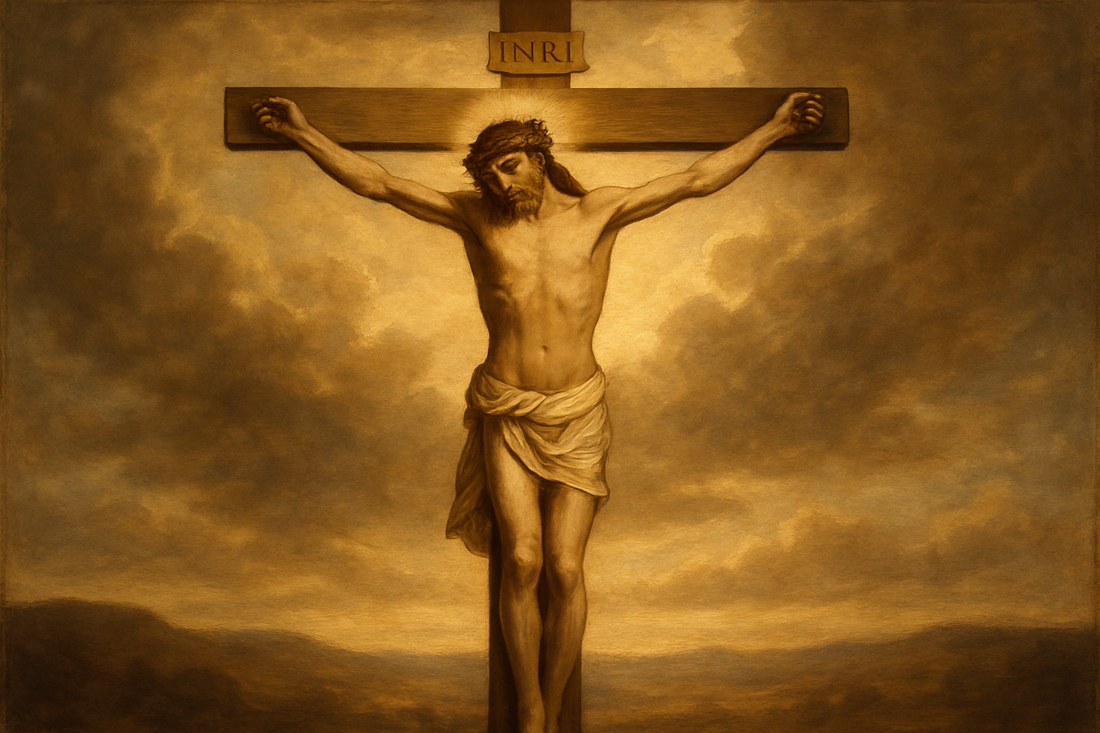

The Three Days Question: Why Christ Was Crucified on Friday (not Wednesday)

Share

In recent years, a theory has gained traction in some Christian circles that Jesus was actually crucified on a Wednesday, not Friday as traditionally held. Proponents argue this resolves the "three days and three nights" puzzle and demonstrate their careful attention to biblical detail. Yet this seemingly minor chronological adjustment carries profound implications for how we understand Scripture, tradition, and the very heart of the Christian story.

The Wednesday Crucifixion Theory

The Wednesday crucifixion argument typically rests on two main pillars. First, its advocates point to Jesus's prophecy in Matthew 12:40: "For just as Jonah was three days and three nights in the belly of the great fish, so will the Son of Man be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth." They argue that a Friday crucifixion and Sunday resurrection cannot accommodate three full days and three full nights (72 hours).

Second, proponents suggest that the "Sabbath" mentioned after Jesus's death was not the regular weekly Sabbath but a special high Sabbath associated with Passover. They propose Jesus died on Wednesday before this special Thursday Sabbath, allowing for the full 72 hours in the tomb before a Saturday evening resurrection. This theory appeals to our modern desire for mathematical precision and our commendable instinct to take Scripture seriously. However, it ultimately misunderstands both ancient Jewish time-reckoning and the unanimous witness of early Christianity.

Understanding Jewish Time-Keeping

To understand why the traditional Friday crucifixion remains the most faithful reading of Scripture, we must first grasp how first-century Jews counted days. In Jewish reckoning, any part of a day counted as a whole day. The Talmud explicitly states this principle: "A day and a night are an Onah ['a portion of time'] and the portion of an Onah is as the whole of it" (Jerusalem Talmud, Shabbath 9:3).

This inclusive counting method appears throughout Scripture. In Genesis 42:17-18, Joseph imprisons his brothers for "three days," yet releases them "on the third day"—not after 72 hours.

Similarly, the Gospel writers consistently use various phrases interchangeably: "after three days" (Mark 8:31), "on the third day" (Luke 9:22), and "three days and three nights" (Matthew 12:40). These all referred to the same time period in Jewish thought: a time span that touches upon three calendar days.

The Unanimous Witness of the Gospels and the Early Church

All four Gospels explicitly state or clearly imply that Jesus was crucified on Friday, the day before the Sabbath. Mark 15:42 states unambiguously: "And when evening had come, since it was the day of Preparation, that is, the day before the Sabbath..."

The Greek word used here, "paraskeué," was the standard term for Friday in first-century Jewish usage. Luke 23:56 reinforces this chronology, noting that the women "rested on the Sabbath according to the commandment" immediately after Jesus's burial.

This was clearly the regular weekly Sabbath, as the commandment to rest specifically refers to the seventh day of the week (Exodus 20:8-11). John’s Gospel, while noting that this particular Sabbath "was a high day" (John 19:31) because it coincided with Passover, still places the crucifixion on "the day of Preparation" (John 19:42).

The weekly Sabbath coinciding with a festival Sabbath made it especially significant, but it doesn't change the day of the week to Wednesday.

Perhaps most compelling is the unanimous testimony of the early Church. The earliest Christians, many of whom were Jewish and all of whom were much closer to the events than we are, universally held that Jesus was crucified on Friday.

The Didache, one of the earliest Christian documents (circa 60–120 AD), instructs Christians to fast on "the fourth day and the Preparation" (Didache 8:1)—that is, Wednesday and Friday—in commemoration of Jesus's betrayal and crucifixion.

Justin Martyr, writing around 150 AD, explicitly states the crucifixion occurred on the day before Saturday and the resurrection on the day after Saturday, which is Sunday. If there had been any confusion about the day of crucifixion, surely some record of debate would have survived. Instead, we find complete unanimity: Jesus died on Friday and rose on Sunday.

Why This Matters

One might ask: does it really matter whether Jesus was crucified on Wednesday or Friday? In one sense, our salvation doesn't depend on getting the chronology perfect. Yet in another sense, this question touches on fundamental issues of how we interpret Scripture and relate to the historic Christian faith.

For biblical interpretation, the Wednesday theory, despite its appeal to biblical literalism, actually imposes a modern, Western understanding of time-keeping onto an ancient Jewish text; true faithfulness requires understanding the text in its original context.

For our connection to the broader Christian tradition, when we casually dismiss two thousand years of unanimous Christian witness in favor of a novel interpretation, we risk an individualism that cuts us off from the wisdom of the communion of saints, as G.K. Chesterton noted, "Tradition means giving votes to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead."

Finally, it matters for the rhythm of Christian worship. The Church has commemorated Good Friday and celebrated Easter Sunday from its earliest days, and these observances flow from the actual sequence of events, keeping us connected to the lived experience of Christians throughout history. The debate over the day of crucifixion ultimately invites us to examine how we approach truth itself, recognizing that the Church's collective memory, guided by the Spirit and tested by time, usually proves more reliable than individual innovation.

Conclusion: The Beauty of the True Story

The traditional understanding—that Jesus was crucified on Friday and rose on Sunday—is not only historically accurate but theologically beautiful, mirroring the pattern of God's work in creation. On Friday (the sixth day of the week), Jesus—the new Adam—completed the work of redemption, echoing the sixth day of creation when God made humanity. He rested in the tomb on the Sabbath (the seventh day), signifying the completion of His work: the Genesis creation was fulfilled, the Exodus liberation was achieved, and the new covenant was sealed.

And on the first day of the new week (Sunday), He rose as the firstfruits of the new creation, ushering in the eighth day—the eternal day of the Lord, where the work of redemption begins its cosmic application. This chronology is more than just accurate; it is providential. It provides a sacred rhythm for Christian life that unites us across two millennia. As believers today, we should cling confidently to the Good Friday tradition, not because we fear novelty, but because we honor the profound integrity of the Gospels and the deep theological truth preserved by the historic Church. The true story is not simply accurate—it is magnificent.

God Bless,

Judah