The Three-Fold Temptation: From Adam to Christ

Share

Have you ever noticed how the same patterns of temptation seem to reappear throughout your life? What if these recurring struggles aren't random but reflect something fundamental about human vulnerability?

The Bible reveals an astonishing consistency in how temptation operates—a pattern that spans from Genesis to Revelation, offering profound insight into both our fallenness and Christ's redemptive work.

If you pay attention, this is the kind of thing that can change your life. Seriously, the reason this devotion is going out so late today is because I just recently discovered all of this and had to process it all (and study it deeper) before I felt comfortable writing to you about it. Let's just say... my mind remains blown.

The Primordial Temptation in Eden

Genesis 3 presents the archetypal temptation narrative. The serpent approaches Eve with a strategy that unfolds in three dimensions:

"When the woman saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was a delight to the eyes, and that the tree was to be desired to make one wise, she took of its fruit and ate" (Gen 3:6)

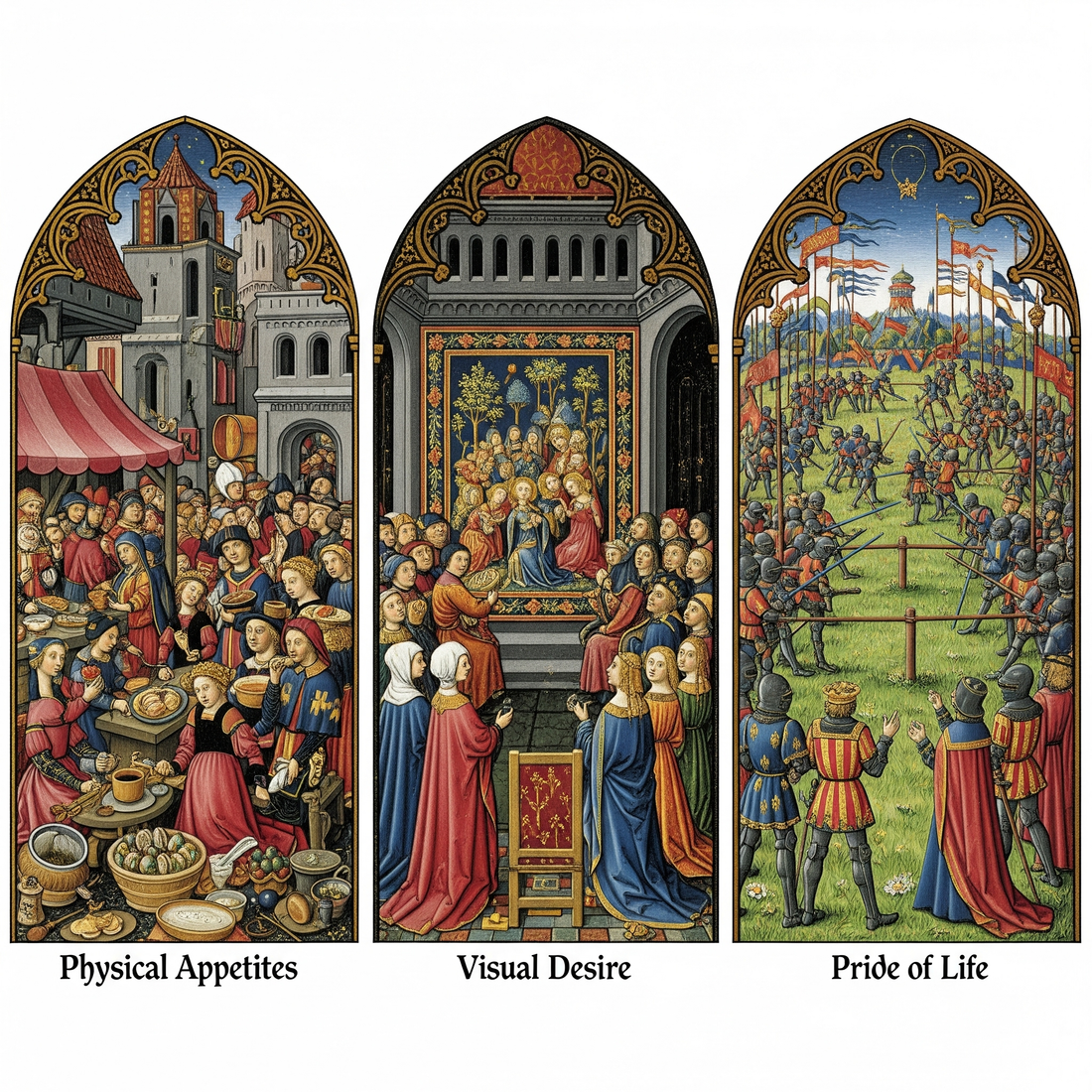

This single verse reveals a three-fold assault:

1. Physical appetite - "good for food" (טוֹב הָעֵץ לְמַאֲכָל)

2. Visual/aesthetic desire - "delight to the eyes" (תַאֲוָה-הוּא לָעֵינַיִם)

3. Intellectual/spiritual pride - "desired to make one wise" (נֶחְמָד הָעֵץ לְהַשְׂכִּיל)

The Hebrew terminology illuminates the depth of this encounter. The term תַאֲוָה (ta'avah) signifies not merely preference but consuming desire—a craving that overrides reason. Meanwhile, נֶחְמָד (neḥmad) conveys something precious, coveted, something that stirs deep longing. This wasn't merely about fruit; it engaged Eve's complete personhood—body, senses, and spirit.

Augustine recognized this pattern as addressing human nature in its totality: the concupiscence of the flesh (physical appetite), the concupiscence of the eyes (sensory desire), and the pride of life (spiritual presumption).

In this primal scene, we witness not merely disobedience but a fundamental reorientation—from God-centeredness to self-centeredness. Eve's reaching for the fruit wasn't simply breaking a rule; it was grasping for self-determination. The temptation wasn't merely to eat forbidden fruit but to "be like God" (Gen 3:5)—to establish autonomy from divine authority.

Christ in the Wilderness: The New Adam Faces Temptation

Fast-forward to the Gospels. After forty days of fasting, Jesus confronts three distinct temptations that parallel Eden's pattern with striking precision:

1. Physical appetite - "command these stones to become loaves of bread" (Mt 4:3)

2. Visual/spectacular display - "throw yourself down" from the temple pinnacle (Mt 4:6)

3. Power/authority - "all the kingdoms of the world and their glory" (Mt 4:8)

The Greek text amplifies the drama. The devil's recurring phrase, "Εἰ υἱὸς εἶ τοῦ θεοῦ" ("If you are the Son of God"), reveals that these aren't merely temptations to sin but challenges to Christ's very identity. Satan's strategy targets not just Jesus' actions but his self-understanding.

Where Adam and Eve fell amid abundance, Jesus stands firm amid scarcity.

Each temptation receives the same response: submission to Scripture. Christ counters not with displays of power but with reverent obedience—"It is written" (γέγραπται).

Irenaeus observed this contrast: the enemy who once used food to persuade a satisfied man to transgress now fails to persuade a hungry man to grasp at food apart from God's provision.

The wilderness confrontation inverts Eden's tragedy. Where Adam reached for godlikeness through disobedience, Christ expresses true divine sonship through perfect submission. Where Adam grasped, Christ yields. Where Adam spoke his own word, Christ speaks only the Father's word.

The Johannine Pattern: Worldly Desires Categorized

In his first epistle, John provides a theoretical framework that crystallizes this pattern with remarkable clarity:

"For all that is in the world—the desires of the flesh and the desires of the eyes and pride of life—is not from the Father but is from the world. And the world is passing away along with its desires, but whoever does the will of God abides forever." (1 Jn 2:16-17)

John's triadic formula presents:

1. ἡ ἐπιθυμία τῆς σαρκός ("the desire of the flesh") - physical appetites

2. ἡ ἐπιθυμία τῶν ὀφθαλμῶν ("the desire of the eyes") - visual/material coveting

3. ἡ ἀλαζονεία τοῦ βίου ("the pride of life") - arrogance of existence

The term ἀλαζονεία (alazoneia) is particularly revealing—denoting not merely pride but boastful arrogance, a pretension to status beyond reality. It captures the essence of sin: the assertion of the self against its proper relation to God.

John's framework isn't merely descriptive but diagnostic. He identifies these desires as "of the world"—not meaning the created order (κόσμος) as God made it, but the fallen system oriented against God's purposes. These desires promise fulfillment but deliver emptiness; they offer life but lead to death.

The contrast couldn't be sharper: these worldly patterns are "passing away" (παράγεται), while "whoever does the will of God abides forever" (μένει εἰς τὸν αἰῶνα). Temporal gratification versus eternal life. Self-determination versus divine alignment.

Christ as the New Adam: Theological Implications

Paul explicitly draws the parallel between Adam's fall and Christ's victory:

"Therefore, as one trespass led to condemnation for all men, so one act of righteousness leads to justification and life for all men. For as by the one man's disobedience the many were made sinners, so by the one man's obedience the many will be made righteous." (Rom 5:18-19)

The linguistic precision is revelatory. The Greek term παρακοή (parakoē, "disobedience") in Romans 5:19 literally means "hearing amiss" or "hearing beside"—suggesting not merely violation but misalignment with God's word. In contrast, Christ's ὑπακοή (hypakoē, "obedience") indicates hearing under authority.

Where Adam grasped at divine prerogatives, Christ "emptied himself, by taking the form of a servant" (Phil 2:7). This reveals that the fundamental human temptation is autonomy—self-definition apart from God. Adam sought to ascend through grasping; Christ descended through giving. Adam reached up in pride; Christ stooped down in humility.

This pattern reveals something profound: sin isn't merely about breaking rules but about breaking relationship. It's about deciding for oneself rather than receiving from God. The essence of temptation is always the same: will we trust God's definition of good or establish our own?

Contemporary Application: The Universal Pattern of Temptation

These three categories illuminate our contemporary experience with startling relevance:

1. Physical appetites - Our culture's fixation on consumption, comfort, and immediate gratification

2. Visual desire - Our susceptibility to image, status, and the power of what we see to shape what we want

3. Pride of life - Our pursuit of achievement, recognition, and self-determination

Consider how these manifest today. The physical appetites aren't merely about food but about all bodily desires—the relentless pursuit of comfort, pleasure, and the avoidance of discomfort at all costs. How often do we make decisions based on what feels good rather than what is good?

The desires of the eyes extend beyond literal vision to acquisitiveness—wanting what we see, whether possessions, experiences, or relationships. In our image-saturated culture, this temptation has unprecedented power. We scroll, we see, we want, we purchase—often without reflection.

The pride of life manifests in our quest for achievement, status, and control—the subtle belief that we can secure our own existence through accomplishment or recognition. It's the whispered promise that with enough success, influence, or power, we can become "someone" who matters. We forget, that we matter already: because God created us in His Image, he gave us a divine calling, to be His image-bearers to the world.

So how do we follow the path of Christ, the new Adam, rather than the old Adam? We draw near to Him. We meditate on his words, like Mary (rather than the busy-body) Martha, and above all, we choose the path of sacrifice. We take up our crosses and follow.

In Jesus' name,

Judah