The Two Castles: The Fear and Love of God

Share

Have you ever watched a skilled tightrope walker perform their craft? High above the ground, they move with a peculiar combination of confidence and caution—every muscle engaged, every step deliberate. They respect the danger without being paralyzed by it. Their healthy fear of falling doesn't come from terror but from a profound understanding of what's at stake. In many ways, this image captures something essential about the spiritual life: we walk a narrow path between presumption and despair, held steady by two forces that might seem contradictory but are actually complementary—the fear and love of God.

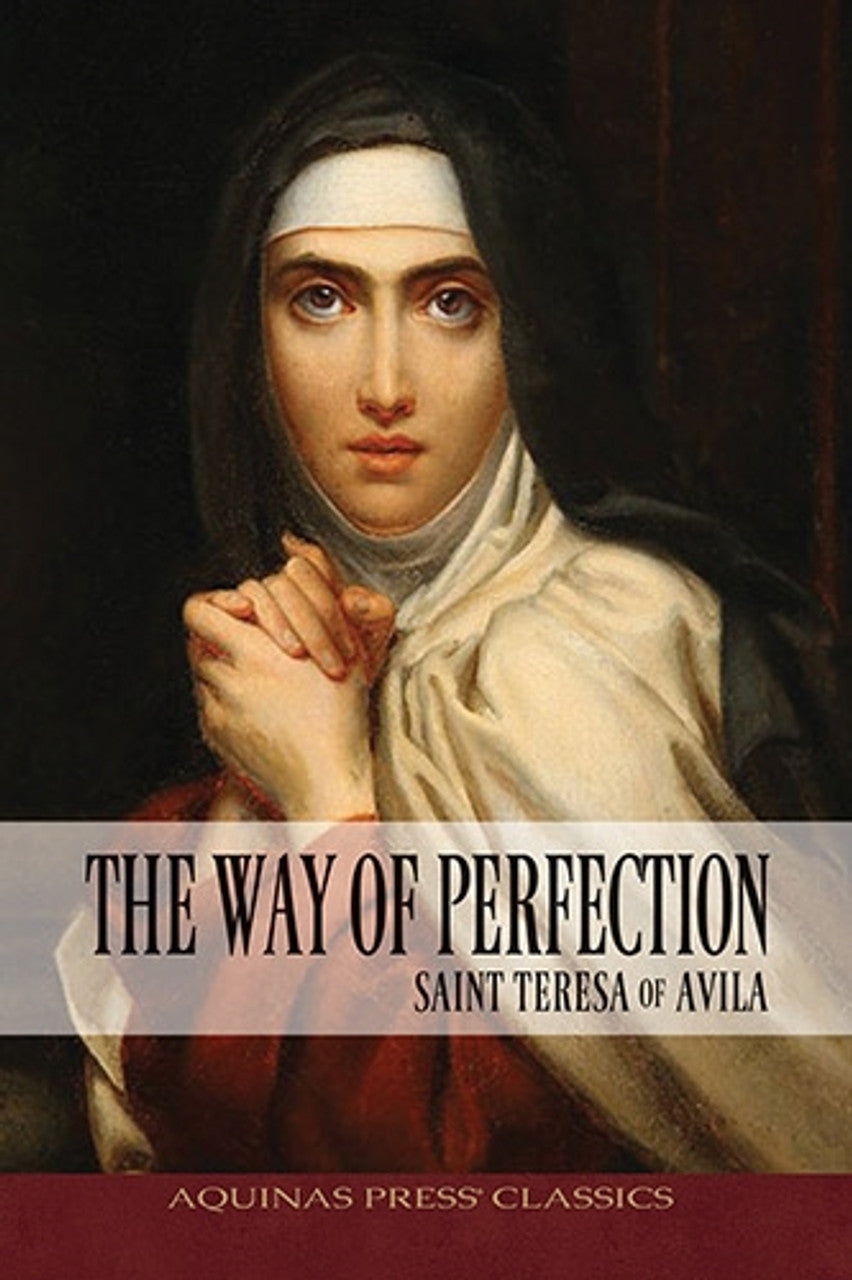

St. Teresa of Ávila, a sixteenth century Carmelite nun, understood this balance with remarkable clarity. In her spiritual classic The Way of Perfection, she presents us with a striking military metaphor: the fear and love of God are like "two strong castles from which we can wage war on the world and on the devils" (Way of Perfection, Chapter 40). This image would have resonated powerfully with her 16th-century readers, familiar with the sight of castles dotting the Spanish landscape. But what might it mean for us today, living in a world where castles have given way to skyscrapers, and where the very notion of fearing God seems antiquated, even offensive?

Understanding Holy Fear

To modern ears, the phrase "fear of God" can sound harsh, even abusive. We've rightly rejected images of God as a cosmic tyrant, waiting to strike down sinners with lightning bolts. Yet Scripture repeatedly insists that "the fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom" (Proverbs 9:10, ESV). The Hebrew word used here, yirah, encompasses more than terror—it includes awe, reverence, and wonder. It's the breathless feeling you might experience standing at the edge of the Grand Canyon or holding a newborn child for the first time.

Consider how the Psalmist expresses this paradox: "Serve the Lord with fear, and rejoice with trembling" (Psalm 2:11, ESV). Notice how fear and rejoicing are held together, not in opposition but in harmony. This isn't the cringing fear of a beaten dog but something far more profound—what theologians call timor filialis, filial fear, the fear of a beloved child.

The analogy of parent and child illuminates this beautifully. Picture a young boy who has just hit a baseball through the neighbor's window. As he walks home, his stomach churns—not primarily because he fears punishment, but because he knows he's disappointed his father. He fears the look of disappointment more than any consequence. This fear springs not from threat but from love. The child who deeply loves his father fears anything that might damage their relationship. As St. Augustine observed, "He who fears to offend, fears to lose" (Sermon 161).

The Fortress of Love

If fear is one castle, love is the other—and ultimately the stronger of the two. The Apostle John tells us that "perfect love casts out fear" (1 John 4:18, ESV), but this doesn't mean love eliminates all types of fear. Rather, as we grow in love, servile fear (the fear of punishment) gradually transforms into filial fear (the fear of separation from the Beloved).

St. Teresa understood that love of God isn't merely an emotion but a fortress—a place of strength from which we can withstand the assaults of temptation and trial. Love provides both motivation and power. As she writes elsewhere, "When we truly love, we find strength to do things that astonish us" (The Interior Castle, VII.4.12).

The Scripture bears witness to love's conquering power. Paul writes to the Romans: "For I am sure that neither death nor life, nor angels nor rulers, nor things present nor things to come, nor powers, nor height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord" (Romans 8:38-39, ESV). This isn't passive sentiment but active, militant love—love that wages war against everything that would separate us from God.

The Strategic Alliance

What makes Teresa's military metaphor so brilliant is her insistence that we need both castles. A military commander wouldn't voluntarily abandon a strategic fortress, and neither should we abandon either fear or love in our spiritual warfare. They work in tandem, each reinforcing the other.

Consider how this plays out practically. When temptation strikes, sometimes it's holy fear that holds us back—the knowledge that sin separates us from God, that it wounds the Body of Christ, that it has real consequences for ourselves and others. The writer of Hebrews warns, "It is a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the living God" (Hebrews 10:31, ESV). This healthy fear can act as an emergency brake when our passions threaten to carry us away.

But fear alone eventually exhausts us. We cannot live perpetually clenched, constantly worried about making mistakes. This is where love takes over. Love provides positive motivation where fear only provides negative restraint. We pursue virtue not merely to avoid punishment but because we want to please the One we love. As St. John Climacus wrote, "Fear makes us flee from sin like slaves, but love makes us run toward virtue like sons" (The Ladder of Divine Ascent, Step 30).

The Dance of Maturation

The relationship between fear and love isn't static—it evolves as we mature spiritually. St. Bernard of Clairvaux identified three stages in this progression. First comes servile fear, where we obey primarily to avoid punishment. Then comes mercenary fear, where we obey to gain rewards. Finally comes filial fear, where we obey purely from love, fearing only to grieve the heart of God (On Loving God, Chapter 9).

This progression mirrors human development. A toddler obeys (when he does) largely from fear of consequences. An older child might obey hoping for rewards. But a mature son or daughter obeys from love, understanding that the parent's commands flow from wisdom and care. The fear remains—but it has been transformed and purified by love.

Jesus himself models this perfect balance. In Gethsemane, we see him in anguish, sweating blood as he contemplates the cup of suffering. "Father, if you are willing, remove this cup from me," he prays (Luke 22:42, ESV). Here is holy fear—not sinful terror, but the natural human recoil from suffering. Yet immediately he adds, "Nevertheless, not my will, but yours, be done." Love conquers fear without eliminating it.

Waging War from the Castles

Teresa's military language reminds us that the spiritual life isn't passive. We are engaged in real combat against real enemies—what traditional theology calls the world, the flesh, and the devil. From our twin castles of fear and love, we wage this war.

Against the world's false promises of happiness through wealth, pleasure, and power, holy fear serves two crucial purposes. First, it reminds us of life's brevity and judgment's certainty. "What does it profit a man to gain the whole world and forfeit his soul?" Jesus asks (Mark 8:36, ESV).

Second, a proper fear of God—the supreme reverence for the Beloved—is the only thing strong enough to cast out all worldly fears. If the only thing we truly stand in awe of, the only separation we dread, is that from God, then what remains to fear in this world? Loss of reputation? Loss of wealth? Loss of comfort? These worldly "fears" represent an imbalanced attachment to things that are passing away. When we fear only offending God, we are liberated from fearing everything else, allowing us to act with spiritual courage and profound interior freedom. But love provides the positive vision—the pearl of great price worth selling everything to obtain.

Against the flesh's disordered desires, fear warns us of sin's enslaving power. Paul writes, "Do you not know that if you present yourselves to anyone as obedient slaves, you are slaves of the one whom you obey?" (Romans 6:16, ESV). Yet love offers something better—the freedom of divine sonship, the joy of virtue, the peace of a well-ordered soul.

Against the devil's lies and accusations, fear keeps us humble and watchful. "Be sober-minded; be watchful. Your adversary the devil prowls around like a roaring lion, seeking someone to devour" (1 Peter 5:8, ESV). But love gives us confidence, knowing that "he who is in you is greater than he who is in the world" (1 John 4:4, ESV).

Practical Applications

How then shall we live? How do we build and maintain these two castles in our daily lives?

First, we must cultivate healthy fear through regular examination of conscience. Each evening, spend a few minutes reviewing your day. Where did you fall short? Where did you grieve God's heart? This isn't meant to produce scrupulosity but honest self-knowledge. As St. Gregory the Great wrote, "The first step of humility is to know oneself" (Moralia in Job, XXIII.13).

Second, we must feed the fire of love through prayer and meditation. Love grows through encounter. We cannot love what we do not know. Daily prayer—not just petition but contemplation—opens us up to the reality of God’s relentless goodness, allowing His perfect love to sink into our hearts, thereby transforming our terror into awe and our anxiety into courageous action.

Conclusion

St. Teresa’s metaphor of the two castles is a masterpiece of spiritual wisdom. It rescues the "fear of God" from antiquated terror and places it in its proper context: an indispensable partner to love. As the tightrope walker respects the ground without being paralyzed by it, we, too, respect the infinite holiness of God without retreating from His presence. We take deliberate, confident steps because we are protected not by one, but by two invincible fortresses: the holy fear that keeps us humble and alert, and the perfect love that casts out crippling terror and motivates us to pursue the Beloved.

May we, like the great saints, learn to wage our spiritual warfare from this strategic alliance, until the day when our journey on the narrow path is complete, and we step fully into the perfect love that is our eternal home.