Three Modes of Prayer: Verbal, Mental, and Contemplative

Share

Over the last couple of days we've looked at the three-fold temptation, the way the devil tempted Eve in the Garden and how temptation follows this same pattern throughout Scripture and also today in our lives! Then, we looked at the three-fold approach to combatting each kind of temptation that Jesus offers in the Sermon on the Mount: Almsgiving, Fasting, and Prayer.

Today, I'd like to spend more time on Prayer. For most of my protestant life, I honestly struggled to pray in a meaningful way. I'd buy devotionals and have good intentions, but I'd usually fall out of the habit before it ever really took root.

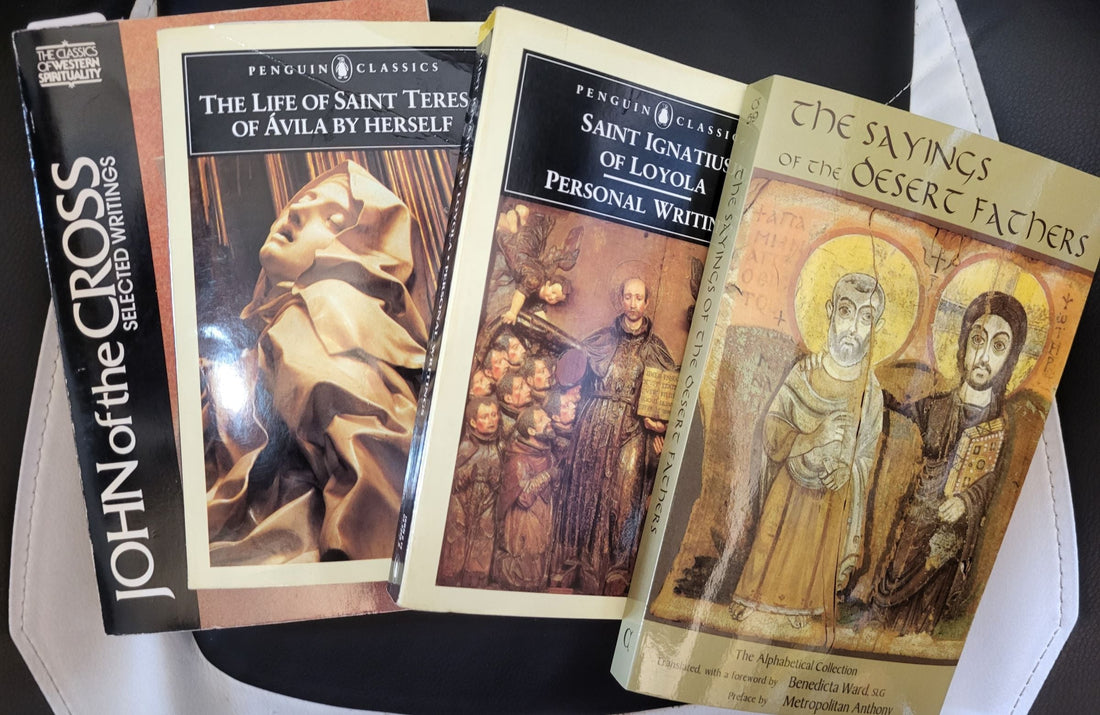

I'm guessing I'm not alone in this. A bit part of my journey over the last few years has been blessed by, frankly, a lot of insight from Christians that pre-dated the Reformation, and others who've come about who are renowned for their spiritual/contemplative lives outside of my tradition. One of the problems (I think) with denominationalism, is that there's so much wisdom in the larger Church that we often turn a blind eye to because they aren't Lutheran, Baptist, Methodist, Presbyterian, Spirit-Filled, or whatever...

For several years, I went through something of a spiritual desert. What St. John of the Cross called a "Dark Night of the Soul," where I struggled to take all my academic knowledge, and my fervent desire to know God more, in a direction that would actually bear fruit in my life. What I've learned isn't something I can really teach in an intellectual way, it's something that has to be practiced.

Nonetheless, I hope this can help you move in the right direction to greater intimacy with God in prayer, and ultimately, experience greater victory over sin and temptation.

Have you ever wondered why prayer sometimes feels like speaking into a void, while at other times it carries you into profound communion with God? That used to be my experience pretty much every time I prayed... which is probably why I struggled to make a habit of it.

The difference may lie not just in what you pray, but in how you pray.

Scripture reveals that prayer is not a monolithic activity but a multifaceted engagement with the divine that involves our entire being—exactly as Jesus commanded when he called us to "love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind and with all your strength" (Mk 12:30).

Verbal Prayer: The Expression of the Lips

When words escape our lips in supplication or praise, we participate in humanity's most fundamental response to God's presence. Throughout Scripture, spoken prayer appears as the natural bridge between human experience and divine reality. The Psalmist captures this beautifully: "O Lord, open my lips, and my mouth will declare your praise" (Ps 51:15).

The Hebrew verb פָּתַח (pāṯaḥ) for "open" suggests not merely the physical parting of lips but the divine enabling that must precede authentic worship. Without God's initiating action, our words remain hollow. This verb appears repeatedly in contexts where God creates possibilities previously closed to humans, emphasizing that verbal prayer itself is a divine gift.

In the New Testament, προσεύχομαι (proseuchomai) describes the act of addressing prayers directly to God, most perfectly exemplified when Jesus taught his disciples to pray, "Our Father in heaven..." (Mt 6:9). This instruction established a pattern for verbal prayer that acknowledges relationship (Father), recognizes divine transcendence (in heaven), and proceeds through specific petitions grounded in God's character.

When we pray verbally, whether through liturgical forms, spontaneous expressions, or Scripture itself, we fulfill part of what it means to love God with our "strength"—employing our physical faculties in divine communication. The Psalms themselves, constituting the Bible's prayer book, predominantly assume verbal expression, showing that God values the articulation of our deepest feelings, from lament to exultation.

When it comes to verbal prayer, it's not about how much you say. Often, fewer words contain more than long drawn-out prayers. Martin Luther put it this way: "The fewer the words, the better the prayer. The more words, the worse the prayer. Few words and much meaning is Christian. Many words and little meaning is pagan" (A Simple Way to Pray, LW 43:193).

While he probably overstates the case (Luther's style uses a lot of hyperbole/exaggeration) the point is plain. The depth of prayer has nothing to do with how many words you use. In other words, verbal prayer's value lies not in eloquence but in sincerity—words that spring from authentic engagement with God.

Sometimes, a single word can speak volumes in prayer. At other times, we feel something inside we can't find the words to speak, so we cry out with a lot of words but those words circle something inside we can't quite pin-point, and by speaking more in those instances we actually invite God who knows our hearts to draw it out and reveal to us not only His will, but the truth of our situation and condition.

Mental Prayer: The Engagement of the Mind

When we move beyond vocalization into thoughtful reflection and meditation on divine truth, we enter the realm of mental prayer—loving God with our minds. The Psalmist describes this mode [though it applies to contemplative prayer too]: "I meditate on your precepts and consider your ways" (Ps 119:15).

The Hebrew verb שִׂיחַ (śîaḥ) translated as "meditate" originally referred to the low murmuring or muttering that accompanied intense thought. It suggests a deep, absorptive engagement with God's revelation—not passive reception but active processing. Similarly, the verb translated as "consider" (אַבִּיטָה, abbîṭāh) conveys attentive examination, suggesting that mental prayer involves careful scrutiny of divine ways.

Mental prayer transforms Scripture from mere text into divine communication. Paul highlights this transformative process: "Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewal of your mind" (Rom 12:2). This renewal occurs precisely when the mind dwells on divine truth, allowing it to challenge and reshape our thinking patterns.

Luther described this mental engagement: "For prayer, as I have said, is not just the movement of the lips, but also, and primarily, the movement of the heart toward God. Indeed, if it does not come from the heart, the movement of the lips is not prayer at all, but empty prattle" (Exposition of Psalm 118, LW 14:55). For Luther, mental prayer represents the heart's authentic turning toward God, without which verbal expressions remain hollow.

This mode of prayer includes theological reflection, scriptural meditation, and the mental wrestling with divine mysteries that characterizes mature faith. When Jesus withdrew to pray, we can imagine not just his spoken words but his profound communion with the Father's will—the mental alignment that enabled him to say, "Not my will, but yours, be done" (Lk 22:42).

Mental prayer develops through practices like lectio divina, where Scripture is slowly read, pondered, and internalized. It flourishes when we ask questions of the text, consider implications, and allow divine wisdom to challenge our assumptions. Through such engagement, we gradually develop what Paul calls "the mind of Christ" (1 Cor 2:16).

Saint Teresa of Avila, a Doctor of the Church known for her teachings on prayer, emphasized mental prayer as a means of growing in intimacy with God. She taught that "Mental prayer, in my opinion, is nothing else than an intimate sharing between friends; it means taking time frequently to be alone with Him who we know loves us." This highlights the personal and relational aspect of mental prayer, not just an intellectual exercise. She further advised, "The important thing is not to think much but to love much." This underscores that the goal of mental prayer is not simply accumulating knowledge, but fostering a loving relationship with God.

Contemplative Prayer: The Surrender of the Heart

Beyond words and thoughts lies a third mode of prayer—contemplative communion that engages the heart's deepest capacity for relationship. Scripture points to this when God says, "Be still, and know that I am God" (Ps 46:10).

The Hebrew imperative הַרְפּוּ (harpû), translated as "be still," literally means to release, let go, or cease striving. This suggests that contemplative prayer begins with surrender—the willingness to release our agenda, our mental constructs, and even our cherished religious language to simply be present with God. This corresponds to Jesus' teaching that true worshipers "will worship the Father in spirit and truth" (Jn 4:23)—a worship that transcends external forms to engage the essential person.

Contemplative prayer finds biblical expression in passages describing wordless communion: "For we do not know what to pray for as we ought, but the Spirit himself intercedes for us with groanings too deep for words" (Rom 8:26). Here, Paul acknowledges a dimension of prayer that exceeds verbal formulation or mental conceptualization—direct spirit-to-Spirit communion.

This mode of prayer develops through practices of silence, stillness, and attentive presence. It flourishes in what the prophet Elijah experienced as "a still small voice" (1 Kgs 19:12)—God's presence perceived not through dramatic manifestations but through subtle awareness. Contemplative prayer trains us to recognize this divine presence in all circumstances, fulfilling Paul's instruction to "pray without ceasing" (1 Thess 5:17).

Luther, despite his emphasis on Scripture's verbal revelation, acknowledged this contemplative dimension: "The heart must become still and quiet to let God speak and to hear Him, as we read in Psalm 46, 'Be still and know that I am God'" (Exposition of Psalm 118, LW 14:50). This recognition that God speaks in stillness affirms the validity of contemplative approaches alongside verbal and mental modes.

Contemplative prayer corresponds to loving God with all our heart—the core of our being where identity and relationship intersect. It acknowledges that God's presence exceeds what words can express or mind can grasp, inviting us into direct, transformative communion.

Saint John of the Cross, a contemporary of Teresa of Avila and also a Doctor of the Church, extensively wrote about contemplative prayer, particularly in his work Dark Night of the Soul. He described it as a passive infused contemplation, where God directly works upon the soul, purifying and transforming it. He famously said, "The soul that is attached to anything, however much good there may be in it, will not arrive at the liberty of divine union. For it matters little whether a bird is tied by a thread or by a chain; it is still tied and cannot fly until the string is broken." This quote speaks to the necessity of detachment and letting go of all created things, even good ones, to enter into deep contemplative union with God.

From the Desert Fathers, early Christian monks and ascetics who lived in the deserts of Egypt and Syria, we find profound insights into stillness and ceaseless prayer. Abba Poemen, a prominent Desert Father, advised, "Sit in your cell, and your cell will teach you everything." This simple counsel points to the importance of inner stillness and solitude as a path to knowing God and oneself. Another saying attributed to a Desert Father is, "A man once asked Abba Sisoes, 'How can I acquire God?' And the old man said, 'If you wish to acquire God, then acquire silence.'" These sayings emphasize the value of profound silence and the cessation of inner chatter as a prerequisite for true contemplation and encountering God.

What's really the difference between mental and contemplative prayer? Well, the mental kind of prayer (which can be like verbal too, when we pray in our minds) that's meditative tends to focus on directing our thoughts toward God, but the contemplative dimension might ruminate more on a particular mystery of the faith, the events of Jesus' life (e.g. the birth of Jesus, his crucifixion, any of his teachings/miracles) in a way that almost "transports" us to the actual events in our minds. Then, in contemplative prayer, we might quiet the mind entirely and allow God to speak.

It's worth noting, since some Christians are uncomfortable about this, that this kind "listening" and "receiving" in prayer isn't about getting new divine revelation that's somehow on-par with Scripture, but it is about hearing more intently what God's will for you is, and how God has brought you into the drama of salvation, how He's gathered your story into His story.

Integration: Praying with the Whole Person

These three modes of prayer—verbal, mental, and contemplative—are not separate activities but interconnected dimensions of our relationship with God. They flow into and enhance one another, just as heart, mind, and strength function together in the integrated person.

Scripture itself models this integration. The Psalms begin with verbal expression that stimulates mental reflection and often culminates in wordless wonder. Jesus' own prayer life demonstrates this progression: from teaching verbal prayers to his disciples (Lk 11:2-4), to engaging in mental prayer through parables and questions (Mt 13:10-17), to withdrawing for contemplative communion with the Father (Mk 1:35).

The ancient practice of lectio divina exemplifies this integration: reading (verbalization) leads to meditation (mental reflection), which opens into contemplation (heartfelt communion), and finally results in action (embodied response). This progression acknowledges that authentic prayer engages our whole being and transforms our entire life.

Integration also occurs across time. Verbal prayer—particularly liturgical forms—provides structure and substance when our hearts feel distant from God. Mental prayer develops theological understanding that prevents contemplative experiences from devolving into emotionalism. Contemplative prayer, in turn, infuses verbal and mental modes with living presence, preventing them from becoming mechanical or merely intellectual.

When Jesus summarized the greatest commandment as loving God with heart, soul, mind, and strength, he was calling for precisely this integration—not compartmentalized devotion but whole-person engagement with divine reality. Prayer that embodies this command will naturally move among verbal, mental, and contemplative modes as circumstances require and as the Spirit leads.

Practical Steps for Lectio Divina

To engage deeply with God's Word through lectio divina, prepare yourself with a quiet space, a Bible, and perhaps a journal and pen. The process traditionally involves four steps, often referred to by their Latin names:

1. Lectio (Reading):

Choose a passage: Select a short passage of Scripture. This could be from the daily liturgical readings, a Psalm, or a passage you feel drawn to. If you're new to this, I suggest starting with the four Gospels and the words of Jesus.

Read slowly and attentively: Read the passage aloud or silently, but at a pace that allows each word to sink in. Don't rush or try to cover a large section. Generally, when I feel like I've got a single "thought" or teaching that's deep enough to reflect on, I let it go. Sometimes that's just one verse, occasionally it's a full chapter. Usually, though, it's short, just a few verses. Read it several times if helpful.

Listen with the "ear of the heart": Pay attention to any word, phrase, or image that stands out to you, resonates deeply, or evokes a particular feeling. This is often where the Holy Spirit is drawing your attention.

2. Meditatio (Meditation):

Ruminate on the chosen word/phrase: Take the word or phrase that caught your attention and ponder it. Chew on it like a cow chews its cud.

Engage your imagination and emotions: What does this word or phrase mean in the context of the passage? How does it relate to your life, your experiences, your current circumstances? What questions does it raise? What feelings does it evoke? Let the text interact with your thoughts, feelings, hopes, and desires. Don't analyze it intellectually as you would for a Bible study, but allow it to penetrate your heart.

3. Oratio (Prayer/Response):

Converse with God: Once you've meditated on the passage, allow your thoughts and feelings to flow into prayer. This is your personal response to what God has spoken to you through the text.

Speak from the heart: Your prayer might be an expression of thanksgiving, repentance, petition, lament, or praise. It could be a simple, spontaneous conversation or a more structured prayer reflecting the themes of the passage. Be honest and open with God about what has been stirred within you.

4. Contemplatio (Contemplation/Rest):

Rest in God's presence: This is a time of simply being with God, beyond words and thoughts. Release your own agenda and expectations.

Be still and receptive: If a particular word or sense of God's presence remains, simply rest in it. There's no need to do anything or think anything specific. It's a moment of loving gaze, a quiet openness to God's transforming love. As the Desert Fathers taught, it is about acquiring silence and simply being present to the Sacred One.

Allow God to work: In this silence, God can deepen the work begun in the previous steps, bringing deeper union and transformation.

Actio (Action) - An Optional Fifth Step:

Many contemporary approaches to lectio divina include a fifth step, Actio, or action. This step recognizes that true prayer should lead to a transformed life.

Discern and live it out. Consider how the insights gained through your prayer can be applied to your daily life. What action, attitude, or change is God inviting you to make? How can you live out the Word you have received? This doesn't have to be a huge thing, it can be a single, small action. It's still a good idea to think about how you can take the insights from your lectio divina practice and live them out. This ensures that lectio divina is not just an internal exercise but a catalyst for living a more Christ-like life in the world.

I hope that helps!!!

In Jesus' name,

Judah