What is the "Communion of Saints"?

Share

Have you ever longed for a deep connection with another person?

Who hasn’t, right? Romance wouldn’t be such a popular genre if we didn’t value human connection. Friendship wouldn’t be so important if connection wasn’t part-and-parcel of how God wired us.

We all crave love. We also know the ache of loss, broken relationships, and loss.

We feel the sting of separation, the ache of loneliness, and perhaps most profoundly, the chasm created by death.

But does the departure of a loved one signify an absolute end to connection? Does the past simply vanish, or is there a living link between yesterday’s faithful and today’s strugglers?

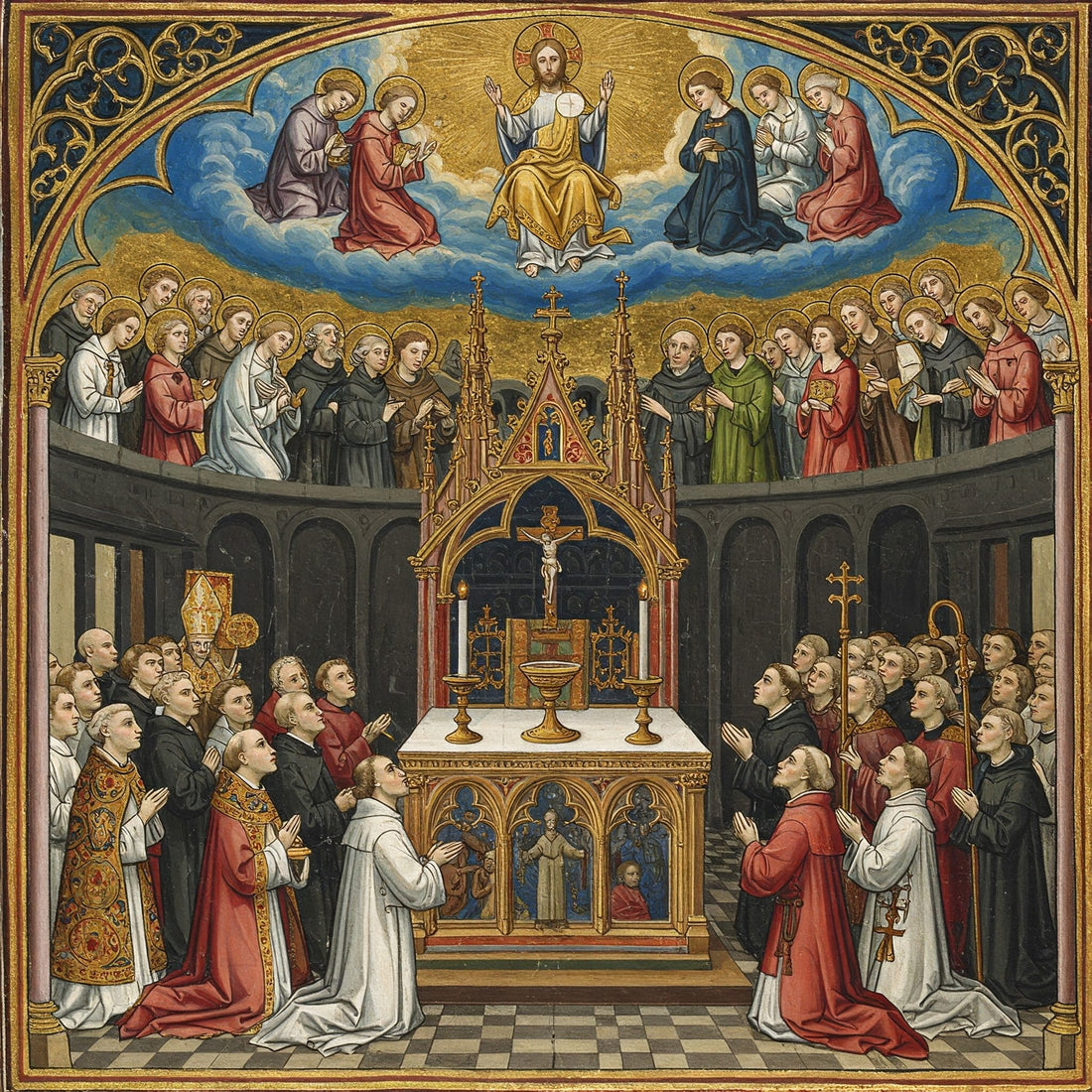

These questions lead us to a cornerstone confession of Christian faith, often recited yet perhaps seldom plumbed: the "communion of saints" (Latin: communio sanctorum).

This phrase, enshrined in the Apostles' Creed, isn't just archaic jargon; it unveils a breathtaking reality about the Church—the very body of Christ—a reality that stretches across continents, centuries, and the veil of death itself.

It also resonates deeply with the enduring command to honor our parents, reminding us to cherish the faithful witness of those who preceded us, not as idols, but as fellow travelers and fellow-witnesses to the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

It’s not just a “Catholic” thing, either (I’m not Catholic). It’s a big part of the New Testament.

The Greek term often associated with it is koinōnia (κοινωνία). This word bursts with meaning: it’s fellowship, participation, sharing, partnership, a joint venture.

It describes the intimate fellowship believers are brought into with God the Father and His Son, Jesus Christ (1 Jn 1:3). It depicts the profound participation in Christ’s body and blood through the Holy Supper (1 Cor 10:16). It signifies the practical sharing of earthly goods among God's people (Acts 2:42; Rom 15:26).

And who are the participants in this koinōnia? They are the hagioi (ἅγιοι), the "holy ones," the "saints."

This term doesn't designate an elite tier of spiritual superstars canonized by human institutions. No, in the New Testament, "saints" refers to all those declared holy by God—not because of their own merits, but because they are washed in the blood of the Lamb (Rev 7:14), set apart through faith in Jesus, and sanctified by the indwelling Holy Spirit (1 Cor 1:2; Eph 1:1).

Thus, the "communion of saints" is the shared life, the mutual indwelling, the profound partnership that binds together everyone God calls holy through His Son.

Does the grave have the final word on fellowship? Can it shatter the unity forged in Christ? The witness of Scripture is an emphatic, resounding "No!"

Listen to the triumphant certainty in Paul's letter to the Romans: "For I am sure that neither death nor life, nor angels nor rulers, nor things present nor things to come, nor powers, nor height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord." (vv 38-39)

Our connection to God is in Christ. Our connection to fellow believers is also fundamentally in Christ.

Therefore, if death cannot sever us from the love of God in Christ, it cannot ultimately sever us from others who abide in that very same love, whether they walk this earth or have entered into His immediate presence. Our koinōnia, our shared life, is anchored in Christ, the one who stared death in the face and emerged victorious (1 Cor 15:54-57).

This enduring connection was deeply understood by theologians of the Reformation era. They grasped that since all believers form one spiritual body with Christ as the Head, death cannot truly sever members from this body. Those who have died in faith remain part of this spiritual organism, sharing in its life through Christ, even as we continue our earthly pilgrimage. The unity is organic, spiritual, inviolable, because it is rooted in the deathless Head of the Church, Jesus Christ.

This perspective is driven home in the Epistle to the Hebrews:

Hebrews 12:22-24 "But you have come to Mount Zion and to the city of the living God, the heavenly Jerusalem, and to innumerable angels in festal gathering, and to the assembly [ἐκκλησίᾳ - ekklēsia] of the firstborn who are enrolled in heaven, and to God, the judge of all, and to the spirits of the righteous made perfect [πνεύμασι δικαίων τετελειωμένων - pneumasi dikaiōn teteleiōmenōn], and to Jesus, the mediator of a new covenant, and to the sprinkled blood that speaks a better word than the blood of Abel."

Consider the astonishing company we keep through faith! The verb tense is critical: "you have come" (προσεληλύθατε - proselēlythate). This is a perfect active indicative, signaling an action completed in the past with results continuing into the present. By faith, we are already participants in this heavenly reality; we have arrived, we belong.

And who populates this glorious assembly? Among others, "the spirits of the righteous made perfect."

The description τετελειωμένων (teteleiōmenōn) is profoundly significant. It's a perfect passive participle derived from the verb τελειόω (teleioō), which means "to complete," "to finish," "to perfect," "to bring to the intended end or goal." These are fellow believers who have completed their earthly journey and have been brought by God Himself to their final state of perfection in His presence.

They are explicitly included within the ekklēsia, the grand assembly, to which we, believers still living on earth, have already come by faith. Death did not eject them from this fellowship; paradoxically, it was the very passage into their perfected state within this same heavenly gathering where Christ reigns supreme.

Our true citizenship is in heaven (Phil 3:20), and the assembly we belong to is ultimately a heavenly one, joyfully encompassing both those still running the race below and those who have crossed the finish line into glory above. They are not gone; they are perfected.

How does this profound communion intersect with the familiar command, "Honor your father and your mother"? (Exod 20:12; Deut 5:16). The Hebrew verb is כַּבֵּד (kabbed), stemming from the root כבד (kbd), which fundamentally means "to be heavy" or "weighty." In the Piel stem, as used here, it takes on an intensive meaning: "treat as weighty," "give significance to," "esteem," "glorify," "honor." This command transcends mere obedience; it calls for deep respect, valuing the God-given position and wisdom vested in parents.

Teachers of the Church have long recognized that the scope of "father and mother" extends beyond biological ties. It encompasses all whom God places in roles of authority and care, including spiritual guides. As Martin Luther explained, we owe honor not only to our earthly parents but also to those who exercise a spiritual "father-office" [Vaterampt], nurturing us in the faith (Large Catechism, Part 1, paras. 141, 158). This naturally includes pastors, teachers, mentors, and, by extension, the historical chain of believers who have faithfully preserved and passed down the Christian faith—our spiritual ancestors.

Therefore, honoring "father and mother" involves honoring our heritage in faith. It means valuing the Church's history, recognizing the painstaking transmission of the Gospel across generations. It calls us to appreciate the insights gleaned by early Church Fathers, the clarity restored by Reformers, and the diligent theological labor of those who defended and articulated the faith grounded solely in Scripture.

However, this honoring must be carefully navigated according to the principle that Scripture alone is the ultimate authority (Sola Scriptura). We honor tradition and our spiritual forebears not as a source of divine revelation parallel or superior to the Bible, but as valuable witnesses to the unchanging truth revealed in the Bible. Their role is servant (ministerial), not master (magisterial). They consistently point us away from themselves and back to the unique, inspired, and infallible Word of God as the sole fountain of doctrine and life.

Consider Paul's instruction in 2 Thessalonians 2:15: "So then, brothers, stand firm and hold to the traditions that you were taught by us, either by our spoken word or by our letter."

Paul urges the Thessalonians to cling firmly to the paradoseis – literally, "the things handed over" or "delivered." In this specific context, emanating directly from an Apostle, this refers to the authoritative apostolic teaching itself—the core of the Gospel message and its practical implications, the very truths that would form the written New Testament.

While some might attempt to leverage this verse to grant post-apostolic human traditions equal footing with Scripture, the Reformation clarified this crucial distinction. There is:

1. The foundational apostolic tradition recorded within Scripture – this we embrace wholeheartedly as God's inspired Word.

2. Historical interpretations, confessions, hymns, and practices that faithfully reflect and are based upon Scripture – these are useful, worthy of respect, and serve the church, but they remain subordinate to and must always be judged by Scripture.

3. Traditions that contradict or obscure Scripture – these must be firmly rejected.

Honoring our fathers and mothers in the faith means cherishing that second category—the faithful witness, the sound doctrine confessed, the godly hymns sung, the insightful commentaries written down through the ages—precisely because they illuminate and help us apply the first category, the unalterable Word of God.

They constitute part of that "great cloud of witnesses" surrounding us, described in Hebrews 12:1. These witnesses are not independent sources of revelation; they are testifiers, bearing witness to God's faithfulness and the power of the faith "once for all delivered to the saints" (Jude 3). Their lives, struggles, and teachings serve as powerful encouragement for us to "run with endurance the race that is set before us, looking to Jesus, the founder and perfecter of our faith" (Heb 12:1-2).

Their testimony doesn't add to the map (Scripture); it helps us read the map correctly.

Think of the difference between looking up how to take a trip on your GPS, or on a map, and hearing about the trip from someone who has driven the journey before. When someone tells you about a trip that they’ve taken, but you haven’t, what they have to say won’t contradict what your GPS says, but it might help illuminate things, show you where you might want to stop and do some sight-seeing, how you might navigate the journey most efficiently (e.g. don’t bother with that pit-stop, they never clean the bathroom!)

The metaphor is imperfect, of course. Someone might add a lot based on their experience that won’t hold true if you take the same path. Maybe they hit a hail storm just outside of Oklahoma City, and when you go through, you have clear skies and sunshine. Maybe they got a flat tire just across the Texas border. That doesn’t mean you will, or that you won’t get a rock in your windshield.

The idea is, though, that we can learn a lot from those who’ve taken the journey ahead of us. We can glean wisdom, even interpretations, that are helpful. For instance, sometimes the GPS is unclear about certain turns related to other turns and landmarks. Someone who has been there might be able to help you out.

In the unchanging landscape of the faith, those who’ve navigated the Scriptures ahead of us, particularly those only a generation or two removed from the actual Apostles, might have a better idea about how something should be interpreted that someone who came up with a new interpretation that no one else ever did 1500 years later.

Its generally a good idea not to adhere to something new, or relatively recent, that hasn’t been taught ever before. Usually, innovative theology is bad theology. That's true 99.9% of the time.

But not everything that’s old is good theology, either. There were errors in the early church, for sure. Usually, though, if you find an error in someone’s theology they tend to stand alone, or in a small crowd, where others have different opinions. There are some issues that are testified to pretty universally in the early church that, if you intend to diverge from, you must assume the burden of proof to show from the Scriptures how they were wrong.

The point is, the communion of saints keeps us humble (or it should) when it comes to developing Christian doctrine, or interpreting passages of the Bible.

For the most part, if I find something that’s universally attested to by the church fathers that I disagree with, I second-guess myself first. There’s a better chance that I messed up somewhere than that every early Christian father who was a lot closer to the apostles than I am did.

In other words, when you read the Bible it's not just you the individual and the Holy Spirit going to town on a text. It's you as a member of the body of Christ (with all those who've gone before you) together with the Holy Spirit who are reading the text.

To put it another way, as a Protestant, I certainly believe in Scripture alone (sola Scriptura) but scripture is never alone. We always read and understand the Scriptures while honoring father and mother, as a part of a long tradition of Christians who've gone before us.

We owe our fellows a certain deference, a bit of respect, and should assume a posture of humility not to think that we know better than everyone else who came before us. We cannot read the Scriptures properly apart from being members of the body of Christ, that is, those who've gone before us (the church triumphant/glorified) and those who remain on earth (the church militant).

Now, there are a lot of issues that come up when the “communion of saints” is discussed. For instance, can the dead in Christ hear us when we pray? For Roman Catholics, who pray “to the saints,” they typically believe that time/space doesn’t separate us from the dead in Christ, meaning we can ask the deceased believers to pray/intercede for us. Protestants tend to disagree with that, on account of scarce biblical evidence that those dead in Christ can hear us when we pray, and because we have no explicit command to do so.

That's my position, too. I think we do have a connection with those who've died in the faith, by virtue of our unity in Christ, but we don't have any explicit command from Christ to pray to them, or any assurance that they can hear us if we ask them to intercede for us. I'm sure some of my Catholic friends will disagree, of course, and that's fine. We can talk about it over coffee sometime.

On the other end of the spectrum, though, sometimes Protestants over-react to old "abuses" of the faith, and end up throwing the whole thing out. For instance, in the Reformation, there was some concern that a belief in transubstantiation led to false idolatry through the adoration of the host. Luther's position, though, was that we shouldn't depart from 1500 years of the universal testimony of the church and make the entire sacrament "symbolic," we should just stop worshipping the host. I'm with Luther on that, too. Jesus tells us how to worship Him in the Lord's Supper: He says take and eat, take and drink. He doesn't say "parade this around and bow down to it."

I'm sure some of you will disagree with me on that, too. But that's a part of what it means to be a part of the communion of saints. We deliberate and discuss our differences not so that we can divide, but because we are one in the body of Christ and all the members should operate in one accord. While there are sad divisions today in the church, that's not the way it should be. We must return to Jesus' plea in his high priestly prayer (John 17) that we might be one, and discuss these differences because of our oneness in Christ, not to win the debate, or prove someone wrong, or so we can put up a video of us "owning" some other Christian in a YouTube debate.

You see, the communion of saints means that we must treat one another charitably, and value even those among us with whom we disagree. Where there are disagreements, we should disagree without ever being disagreeable. We might not realize a perfect earthly unity here and now, until Jesus comes back and clears everything up, but we should still pursue it vigorously.

I recognize the idea of the "communion of the saints" might be foreign to some of you, and parts of it might even make you uncomfortable. The doctrine has been abused, and taken too far (I would suggest) at times.

However, we shouldn’t throw the baby out with the bathwater. The reality of the communion of saints is an immense comfort. It means that death doesn’t separate us from our loved ones when they pass. It means not only that we’ll get to see them again, but that we still share something in common with them here and now by virtue of being members of the body of Christ. It means, in a very real sense, we’re still connected.

It also means that there’s no such thing as “lone ranger” Christianity. You can’t lay “dibs” on one part of Christ’s body and call it yours, like his little toe or something, and keep everyone else out. We are all full members of His singular body, and we are meant to function as one. Thus, we must always strive for greater unity, we should treat one another with charity (the hand should never cut off the foot, for by so doing the entire body suffers!).

In Jesus' name,

Judah